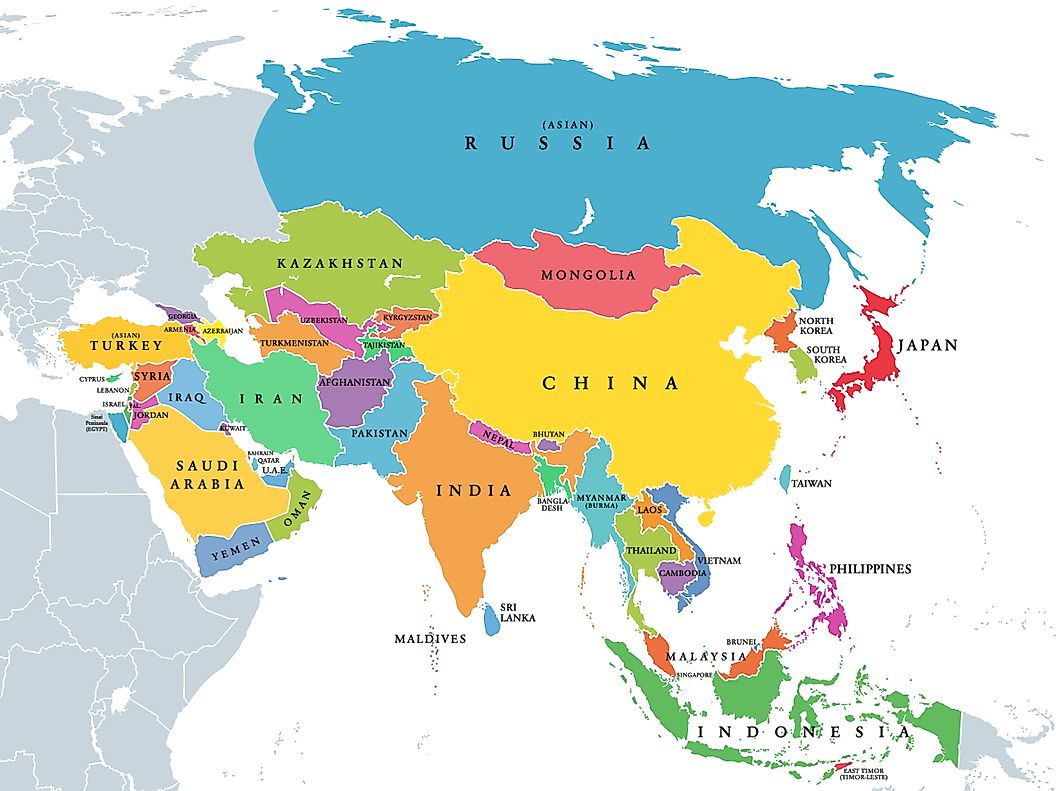

Asia, the world’s largest and most diverse continent. It occupies the eastern four-fifths of the giant Eurasian landmass. Asia is more a geographic term than a homogeneous continent, and the use of the term to describe such a vast area always carries the potential of obscuring the enormous diversity among the regions it encompasses. Asia has both the highest and the lowest points on the surface of Earth, has the longest coastline of any continent, is subject overall to the world’s widest climatic extremes, and, consequently, produces the most varied forms of vegetation and animal life on Earth. In addition, the peoples of Asia have established the broadest variety of human adaptation found on any of the continents.

The name Asia is ancient, and its origin has been variously explained. The Greeks used it to designate

the lands situated to the east of their homeland. It is believed that the name may be derived from the

Assyrian word asu, meaning “east.” Another possible explanation is that it was originally a local name

given to the plains of Ephesus, which ancient Greeks and Romans extended to refer first to Anatolia

(contemporary Asia Minor, which is the western extreme of mainland Asia), and then to the known world

east of the Mediterranean Sea. When Western explorers reached South and East Asia in early modern times,

they extended that label to the whole of the immense landmass.

Asia is bounded by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Pacific Ocean to the east, the Indian Ocean to the

south, the Red Sea (as well as the inland seas of the Atlantic Ocean—the Mediterranean and the Black) to

the southwest, and Europe to the west. Asia is separated from North America to the northeast by the

Bering Strait and from Australia to the southeast by the seas and straits connecting the Indian and

Pacific oceans. The Isthmus of Suez unites Asia with Africa, and it is generally agreed that the Suez

Canal forms the border between them. Two narrow straits, the Bosporus and the Dardanelles, separate

Anatolia from the Balkan Peninsula.

The land boundary between Asia and Europe is a historical and cultural construct that has been defined variously; only as a matter of agreement is it tied to a specific borderline. The most convenient geographic boundary—one that has been adopted by most geographers—is a line that runs south from the Arctic Ocean along the Ural Mountains and then turns southwest along the Emba River to the northern shore of the Caspian Sea; west of the Caspian, the boundary follows the Kuma-Manych Depression to the Sea of Azov and the Kerch Strait of the Black Sea. Thus, the isthmus between the Black and Caspian seas, which culminates in the Caucasus mountain range to the south, is part of Asia.

The total area of Asia, including Asian Russia (with the Caucasian isthmus) but excluding the island of

New Guinea, amounts to some 17,226,200 square miles (44,614,000 square km), roughly one-third of the

land surface of Earth. The islands—including Taiwan, those of Japan and Indonesia, Sakhalin and other

islands of Asian Russia, Sri Lanka, Cyprus, and numerous smaller islands—together constitute 1,240,000

square miles (3,210,000 square km), about 7 percent of the total. (Although New Guinea is mentioned

occasionally in this article, it generally is not considered a part of Asia.) The farthest terminal

points of the Asian mainland are Cape Chelyuskin in north-central Siberia, Russia (77°43′ N), to the

north; the tip of the Malay Peninsula, Cape Piai, or Bulus (1°16′ N), to the south; Cape Baba in Turkey

(26°4′ E) to the west; and Cape Dezhnev (Dezhnyov), or East Cape (169°40′ W), in northeastern Siberia,

overlooking the Bering Strait, to the east.

Asia has the highest average elevation of the continents and contains the greatest relative relief. The

tallest peak in the world, Mount Everest, which reaches an elevation of 29,035 feet (8,850 metres; see

Researcher’s Note: Height of Mount Everest); the lowest place on Earth’s land surface, the Dead Sea,

measured in the mid-2010s at about 1,410 feet (430 metres) below sea level; and the world’s deepest

continental trough, occupied by Lake Baikal, which is 5,315 feet (1,620 metres) deep and whose bottom

lies 3,822 feet (1,165 metres) below sea level, are all located in Asia. Those physiographic extremes

and the overall predominance of mountain belts and plateaus are the result of the collision of tectonic

plates. In geologic terms, Asia comprises several very ancient continental platforms and other blocks of

land that merged over the eons. Most of those units had coalesced as a continental landmass by about 160

million years ago, when the core of the Indian subcontinent broke off from Africa and began drifting

northeastward to collide with the southern flank of Asia about 50 million to 40 million years ago. The

northeastward movement of the subcontinent continues at about 2.4 inches (6 cm) per year. The impact and

pressure continue to raise the Plateau of Tibet and the Himalayas.

Asia’s coastline—some 39,000 miles

(62,800 km) in length—is, variously, high and mountainous, low and

alluvial, terraced as a result of the land’s having been uplifted, or “drowned” where the land has

subsided. The specific features of the coastline in some areas—especially in the east and southeast—are

the result of active volcanism; thermal abrasion of permafrost (caused by a combination of the action of

breaking waves and thawing), as in northeastern Siberia; and coral growth, as in the areas to the south

and southeast. Accreting sandy beaches also occur in many areas, such as along the Bay of Bengal and the

Gulf of Thailand.

The mountain systems of Central Asia not only have provided the continent’s great rivers with water from

their melting snows but also have formed a forbidding natural barrier that has influenced the movement

of peoples in the area. Migration across those barriers has been possible only through mountain passes.

A historical movement of population from the arid zones of Central Asia has followed the mountain passes

into the Indian subcontinent. More recent migrations have originated in China, with destinations

throughout Southeast Asia. The Korean and Japanese peoples and, to a lesser extent, the Chinese have

remained ethnically more homogeneous than the populations of other Asian countries.

Asia’s population is unevenly distributed, mainly because of climatic factors. There is a concentration

of population in western Asia as well as great concentrations in the Indian subcontinent and the eastern

half of China. There are also appreciable concentrations in the Pacific borderlands and on the islands,

but vast areas of Central and North Asia—whose forbidding climates limit agricultural productivity—have

remained sparsely populated. Nonetheless, Asia, the most populous of the continents, contains some

three-fifths of the world’s people.

Asia is the birthplace of all the world’s major religions—Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, and

Judaism—and of many minor ones. Of those, only Christianity developed primarily outside of Asia; it

exerts little influence on the continent, though many Asian countries have Christian minorities.

Buddhism has had a greater impact outside its birthplace in India and is prevalent in various forms in

China, South Korea, Japan, the Southeast Asian countries, and Sri Lanka. Islam has spread out of Arabia

eastward to South and Southeast Asia. Hinduism has been mostly confined to the Indian subcontinent.

| Subject | Value |

|---|---|

| Most Renewable Electricity Produced | Bhutan (99.9%, hydropower) |

| Population Density | 246 people per square kilometer |

| Largest Watershed | Ob River (3 million square kilometers/1.15 million square miles) |

| Highest Elevation | Mount Everest, Nepal: 8,848 meters/29,029 feet |

| Largest Urban Area | Tokyo-Yokohama, Japan (37.8 million people) |

Asia is not only Earth’s largest continent but also its youngest and structurally most-complicated one. Although Asia’s evolution began almost four billion years ago, more than half of the continent remains seismically active, and new continental material is currently being produced in the island arc systems that surround it to the east and southeast. In such places, new land is continuously emerging and is added to the bulk of the continent by episodic collisions of the island arcs with the mainland. Asia also contains the greatest mountain mass on Earth’s surface: the Plateau of Tibet and the bordering mountains of the Himalayas, Karakoram Range, Hindu Kush, Pamirs, Kunlun Mountains, and Tien Shan. By virtue of its enormous size and relative youth, Asia contains many of the morphological extremes of Earth’s land surface—such as its highest and lowest points, longest coastline, and largest area of continental shelf. Asia’s immense mountain ranges, varied coastline, and vast continental plains and basins have had a profound effect on the course of human history. The fact that Asia produces vast quantities of fossil fuels—petroleum, natural gas, and coal—in addition to being a significant contributor to the global production of many minerals (e.g., about three-fifths of the world’s tin) heavily underlines the importance of its geology for the welfare of the world’s population.

The morphology of Asia masks an extremely complex geologic history that predates the active

deformations

largely responsible for the existing landforms. Tectonic units (regions that once formed or now form

part of a single tectonic plate and whose structures derive from the formation and motion of that

plate)

that are defined on the basis of active structures in Asia are not identical to those defined on the

basis of its fossil (i.e., now inactive) structures. It is therefore convenient to discuss the

tectonic

framework of Asia in terms of two separate maps, one showing its paleotectonic (i.e., older

tectonic)

units and the other displaying its neotectonic (new and presently active) units.According to the

theory

of plate tectonics, forces within Earth propel sections of its crust on various courses, with the

result

that continents are formed and oceans are opened and closed.

Oceans commonly open by rifting—by

tearing

a continent asunder—and close along subduction zones, which are inclined planes along which ocean

floors

sink beneath an adjacent tectonic plate and are assimilated into Earth’s mantle. Ocean closure

culminates in continental collision and may involve the accretion of vast tectonic collages,

including

small continental fragments, island arcs, large deposits of sediment, and occasional fragments of

ocean-floor material. In defining the units to draw Asia’s paleotectonic map, it is useful to

outline

such accreted objects and the lines, or sutures, along which they are joined.Continuing convergence

following collision may further disrupt an already assembled tectonic collage along new, secondary

lines, especially by faulting. Postcollisional disruption also may reactivate some of the old

tectonic

lines (sutures). Those secondary structures dominate and define the neotectonic units of Asia. It

should

be mentioned, however, that most former continental collisions also have led to the generation of

secondary structures that add to the structural diversity of the continent.The paleotectonic units

of

Asia are divided into two first-order classes: continental nuclei and orogenic (mountain-building)

zones. The continental nuclei consist of platforms that stabilized mostly in Precambrian time

(between

roughly 4 billion and 541 million years ago) and have been covered largely by little-disturbed

sedimentary rocks; included in that designation are the Angaran (or East Siberian), Indian, and

Arabian

platforms.

There are also several smaller platforms that were deformed to a greater extent than the

larger units and are called paraplatforms; those include the North China (or Sino-Korean) and

Yangtze

paraplatforms, the Kontum block (in Southeast Asia), and the North Tarim fragment (also called

Serindia;

in western China). The orogenic zones consist of large tectonic collages that were accreted around

the

continental nuclei. Recognized zones are the Altaids, the Tethysides (further subdivided into the

Cimmerides and the Alpides), and the circum-Pacific belt. The Alpides and circum-Pacific belt are

currently undergoing tectonic deformation—i.e., they are continuing to evolve—and so are the

locations

of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions.The Precambrian continental nuclei were formed by essentially

the

same plate tectonic processes that constructed the later orogenic zones, but it is best to treat

them

separately for three reasons. First, the nuclei occupy only about one-fourth of the area of Asia,

and

less than one-third of that area (i.e., less than 10 percent of Asia’s total) consists of exposed

Precambrian rocks that enable geologists to study their development. Second, Precambrian rocks are

extremely poor in fossils, which makes global or even regional correlations difficult. Finally,

during

most of Phanerozoic time (i.e., about the past 541 million years), the nuclei have remained stable

and

have acted as hosts around which the tectonic collages have accumulated in the Phanerozoic orogenic

zones.

The paleotectonic evolution of Asia terminated some 40 to 50 million years ago as a result of

the

collision of the Indian subcontinent with Eurasia. Asia’s subsequent neotectonic development has

largely

disrupted the continent’s preexisting fabric. The first-order neotectonic units of Asia are Stable

Asia,

the Arabian and Indian cratons, the Alpide plate boundary zone (along which the Arabian and Indian

platforms have collided with the Eurasian continental plate), and the island arcs and marginal

basins.

The oldest rocks in Asia are found in the continental nuclei. Rocks more than 3 billion years old

are in

the Precambrian outcrops of the Angaran and Indian platforms and in the North China paraplatform.

They

consist of primitive island-arc magmatic and sparse sedimentary rocks sandwiched between younger

basaltic and ultrabasic rocks, exposed along what are called greenstone belts. The basement of the

Angaran platform was largely formed by about 1.5 billion years ago. The final consolidation of the

Indian platform, however, lasted until about 600 million years ago and included various

mountain-building episodes with peaks of activity between 2.4 and 2.3 billion years ago, at about 2

billion years ago, between 1.7 and 1.6 billion years ago, and between 1.1 billion and 600 million

years

ago. In the Arabian platform the formation of the present basement commenced by arc and

microcontinent

accretion some 900 million years ago and ended about 600 million years ago, although some of the

accreted microcontinents had basements more than 2.5 billion years old and may be detached fragments

of

Africa.While other Asian continental nuclei were completing their consolidation, orogenic

deformation

recommenced along the present southeast and southwest margins of the Angaran platform. That renewed

activity marked the beginning of a protracted period of subduction, the development of vast

sedimentary

piles scraped off sinking segments of ocean floor in subduction zones and accumulated in the form of

subduction-accretion wedges at the leading edge of overriding plates, and subduction-related

magmatism

and numerous collisions in what today is known as Altaid Asia (named for the Altai Mountains).

Orogenic

deformation in the Altaids was essentially continuous from the late Proterozoic Eon (about 850

million

years ago) into the early part of the Mesozoic Era (about 220 million years ago), in some

regions—such

as Mongolia and Siberia—lasting even to the end of the Jurassic Period (about 145 million years

ago).

The construction of the Altaid collage was coeval with the late Paleozoic assembly of the Pangea (or

Pangaea) supercontinent (between about 320 and 250 million years ago). The Altaids lay to the north

of

the Paleo-Tethys Ocean (also called Paleo-Tethys Sea), a giant triangular eastward-opening embayment

of

Pangea. A strip of continental material was torn away from the southern margin of the Paleo-Tethys

and

migrated northward, rotating around the western apex of the Tethyan triangle much like the action of

a

windshield wiper. That continental strip, called the Cimmerian continent, was joined during its

northward journey by a collage of continental material that had gathered around the Yangtze

paraplatform

and the Kontum block, and, between about 210 and 180 million years ago, all of that material

collided

with Altaid Asia to create the Cimmeride orogenic belt.

While the Cimmerian continent was drifting northward, a new ocean, the Neo-Tethys, was opening

behind it

and north of the Gondwanaland supercontinent. The new ocean began closing some 155 million years

ago,

shortly after the beginning of the major disintegration of Gondwanaland. Two fragments of

Gondwanaland,

India and Arabia, collided with the rest of Asia during the Eocene (i.e., about 56 to 34 million

years

ago) and the Miocene (about 23 to 5.3 million years ago) epochs, respectively. The orogenic belts

that

arose from the destruction of the Neo-Tethys and the resultant continental collisions are called the

Alpides and form the present Alpine-Himalayan mountain ranges. Both the Cimmerides and the Alpides

resulted from the elimination of the Tethyan oceans, and collectively they are called the

Tethysides.

Most of the island arcs fringing Asia to the east came into being by subduction of the Pacific Ocean

floor and the opening of marginal basins behind those arcs during the Cenozoic Era (the past 66

million

years). That activity continues today and is the major source of tectonism (seismic and volcanic

activity often resulting in uplift) in South and Southeast Asia. In the south and in the southwest,

India and Arabia are continuing their northward march, moving at an average of about 2.4 and 1.6

inches

(6 and 4 cm), respectively, per year. Those movements have caused the massive distortion of the

southern

two-thirds of Asia and produced the nearly continuous chain of mountain ranges between Turkey and

Myanmar (Burma) that in places widen into high plateaus in Turkey, Iran, and the Tibet Autonomous

Region

of China. Within and north of those plateaus, geologically young mountains such as the Caucasus and

the

Tien Shan, large strike-slip faults such as the North Anatolian and the Altun (Altyn Tagh), and rift

valley basins such as Lake Baikal—all of which are associated with seismic activity—bear witness to

the

widespread effects of the convergence of Arabia and India with Stable Asia, in which no notable

active

tectonism is seen.

Characteristic of the surface of Asia is the great predominance of mountains and plateaus, constituting about three-fourths of the continent’s total area. The mountains are grouped into two belts: those located on the stable platforms (cratons) and those located in active orogenic zones. The former usually occur on the margins of the platforms and generally are characterized by smooth eroded peaks and steep faulted slopes. Marginal mountain ranges, with average heights of 8,200 to 9,850 feet (2,500 to 3,000 metres), usually enclose the inner tablelands and plateaus; examples of such ranges include the Western and Eastern Ghats in India, the mountains of the Hejaz and Yemeni highlands on the Arabian Peninsula, and the Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon mountains in the Levant. The Aldan Plateau and Stanovoy Range lie along the eastern margin of the Angaran (Siberian) platform, where the isolated and uplifted Putoran Mountains are located in central Siberia.Mountains of the orogenic zones are much higher in elevation and have a more-complicated structure. Tectonic movements in those zones have given rise to structures of different age and composition. Mesozoic and Cenozoic foldings (i.e., those of roughly the past 250 million years) created boundaries between basic types of mountains over vast areas of Asia. The largest mountain belt on Mesozoic structures (i.e., from about 252 to 66 million years ago) extends from the Chukchi Peninsula at the eastern extremity of Asia through the Kolyma Upland and the Dzhugdzhur and Stanovoy ranges to the mountains of southern Siberia (the Sayan and the Altai mountains) and to the Tien Shan and Gissar-Alay ranges. The Chersky and Verkhoyansk ranges are the western spurs of that belt.Along the edges of the Central Asian plateaus extend the elongated mountain chains of the Da Hinggan (Greater Khingan), Taihang, and Daxue ranges. The Hinggan-Bureya mountains (Xiao Hinggan [Lesser Khingan] and Bureya ranges) demarcate the Zeya-Bureya Depression. The Manchurian-Korean and Sikhote-Alin mountain ranges separate the plains of the Amur and Sungari (Songhua) rivers, the Lake Khanka lowland, and the Northeast (Manchurian) Plain. The coastal ranges in the southeast consist of the mountains of southern China and the Annamese Cordillera. A generally latitudinal branch springs from the Pamirs region and runs eastward through the Kunlun, Qilian, and Qin (Tsinling) mountains.The Alpine-Himalayan mountain belt runs in a west-east direction and includes the Taurus Mountains, the Caucasus, the Zagros and Elburz mountains, the Hindu Kush, the Pamirs, the Karakoram Range, the Plateau of Tibet, and the Himalayas; it then turns to the south and southeast, running through the Rakhine (Arakan) Mountains to the islands of the Malay Archipelago. The western part of that belt consists, for a considerable distance, of two series of mountain chains that converge in dense knots in the Armenian Highland, in the Pamirs, and in the southeast of the Plateau of Tibet; the two chains then diverge to encompass the interior plateaus. The average elevation of highlands and marginal ranges increases from west to east from about 2,600 to 3,000 feet (800 to 900 metres) on the Anatolian Plateau to about 13,000 to 16,400 feet (4,000 to 5,000 metres) on the Plateau of Tibet and from about 8,200 to 11,500 feet (2,500 to 3,500 metres) in the Pontic and Taurus mountains to 19,000 feet (5,800 metres) in the Himalayas.On the northeastern and eastern edges of Asia, a vast belt of Cenozoic Era (i.e., of the past 66 million years) folding extends from the Koryak Mountains of the Kamchatka-Koryak arc along the Sredinny (Central) range on the Kamchatka Peninsula of Russia. The marginal seas of the western Pacific Ocean are bordered by the East Asian islands, which form the line of arcs running from the Kamchatka Peninsula in the north to the Sunda Islands of Indonesia in the south. Many of those islands are part of the Ring of Fire, a belt of volcanic and seismic activity in the Pacific Rim.

Low plains occupy the rest of the Asian mainland, particularly the vast West Siberian and Turan

plains

of the interior. The remaining lowlands are distributed either in the maritime regions—such as the

North

Siberian and Yana-Indigirka lowlands and the North China Plain—or in the piedmont depressions of

Mesopotamia, the Indo-Gangetic Plain, and mainland Southeast Asia. Those plains have monotonously

level

surfaces with wide valleys, through which the great Asian rivers and their tributaries flow. The

topography of the plains in densely populated regions has been greatly modified through the

construction

of canals, dams, and levees. To the south of the zone of piedmont depressions lie extensive

tablelands

and plateaus, including the Deccan plateau in India and the Syrian-Arabian Plateau in the west. In

addition, there are the intermontane basins of Kashgaria, Junggar, Qaidam (Tsaidam), and Fergana and

the

plateaus of central Siberia and the Gobi, all of which lie at elevations of 2,600 to 4,900 feet (800

to

1,500 metres). Most of their surfaces are smooth or gently rolling, with isolated hillocks. The

plateaus

inside the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, the Tien Shan, and the Pamirs lie at elevations of some

12,000 feet (3,700 metres) or more.

A large proportion of the islands of Asia are mountainous. The highlands of Sri Lanka rise to 8,281

feet

(2,524 metres); Mount Kinabalu in Malaysia reaches 13,455 feet (4,101 metres); Mount Fuji on the

Japanese island of Honshu has an elevation of 12,388 feet (3,776 metres); and numerous volcanoes on

Sumatra, Java, and Mindanao reach 10,000 feet (3,000 metres). Among the active volcanoes associated

with

the Ring of Fire are Krakatoa on Rakata Island in Indonesia, Mount Pinatubo on Luzon in the

Philippines,

and Mount Aso on Kyushu in Japan.

The contemporary relief of Asia was molded primarily under the influences of (1) ancient

processes

of planation (leveling), (2) larger vertical movements of the surface during the Cenozoic Era,

and

(3) severe erosive dissection of the edges of the uplifted highlands with the accompanying

accumulation of alluvium in low-lying troughs, which were either settling downward or being

uplifted

more slowly than the adjoining heights.The interior portions of the uplifted highlands and the

plateaus and tablelands of peninsular India, Arabia, Syria, and eastern Siberia—all of which are

relatively low-lying but composed of resistant rock—largely have preserved their ancient peneplaned

(i.e., leveled) surfaces. Particularly spectacular uplifting occurred in Central Asia, where the

amplitude of uplift of the mountain ranges of Tibet and of the Pamirs and the Himalayas has exceeded

13,000 feet (4,000 metres). The eastern margin of the highlands, meanwhile, underwent subsidences of

up to 2,300 feet (700 metres). Uplifting as a result of fractures at great depths, of which the

Kopet-Dag and ranges surrounding the Fergana Valley provide typical examples, and of folding over a

large radius, examples of which may be seen in the Tien Shan and Gissar and Alay ranges, played a

significant role.Erosional dissection transformed many ancient plateaus into mountainous regions.

Majestic gorges were carved into the highlands of the western Pamirs and southeastern Tibet; the

Himalayas, the Kunlun and Sayan mountains, the Stanovoy and Chersky ranges, and the marginal ranges

of the West Asian highlands were deeply cut by the rivers, which created deep superimposed gorges

and canyons.Vast areas of Middle, Central, and East Asia, particularly in the Huang He (Yellow

River) basin, are covered with loess (a loamy unstratified deposit formed by wind or by glacial

meltwater deposition); the thickness of the deposits on the Loess Plateau of China sometimes exceeds

1,000 feet (300 metres). There are broad expanses of badlands, eolian (wind-produced) relief, and

karst topography (limestone terrain associated with vertical and underground drainage). Karst

terrain is characteristic of the Kopet-Dag, the eastern Pamirs, the Tien Shan, the Gissar and Alay

ranges, the Ustyurt Plateau, the western Taurus Mountains, and the Levant. Tropical karst (limestone

landscape) in South China is renowned for its picturesque residual hills.

The mantle of glaciation from the Pleistocene Epoch (i.e., about 2,600,000 to 11,700 years ago)

embraced northwestern Asia only to latitude 60° N. East of the Khatanga River, which flows from

Siberia into the Arctic Ocean, only isolated glaciation of the mantle debris and of the mountains

occurred, because of the extremely dry climate that existed in northeastern Asia even at that time.

The high mountain regions experienced primarily mountain glaciation. There are traces of several

periods during which the glaciers advanced—periods separated by warmer interglacial epochs.

Glaciation continues in many of the mountainous areas and on the Severnaya Zemlya archipelago. The

Karakoram Range, the Pamirs, the Tien Shan, the Himalayas, and the eastern Hindu Kush are noted for

the immensity of their contemporary glaciers. Most of the glaciers are retreating. The elevation of

the permanent snow line is relatively high, averaging between 14,800 and 16,400 feet (4,500 and

5,000 metres) and reaching 21,000 feet (6,400 metres) in central Tibet.

An enormous area of permafrost—some 4.25 million square miles (11 million square km)—covers northern

Asia and extends to lower latitudes there than anywhere else in the world. Little snowfall occurs,

because of the aridity, and deep freezing of the soil takes place. The depth of the permafrost in

continental northern and eastern Siberia exceeds 1,000 to 1,300 feet (300 to 400 metres).Volcanism

has added broad lava plateaus and chains of young volcanic cones to the relief of Asia. Ancient

lavas and intrusions of magma, exposed by later erosion, cover the terraced plateaus of peninsular

India and central Siberia. Extensive zones of young volcanic relief and contemporary volcanism,

however, are confined to the unstable arcs of the East Asian islands, together with the Kamchatka

Peninsula, the Philippines, and the Sunda Islands. The highest active volcano in Asia,

Klyuchevskaya, rises to 15,584 feet (4,750 metres) on Kamchatka.Geologically recent volcanism is

also characteristic of the West Asian highlands, the Caucasus, Mongolia, the Manchurian-Korean

mountains, and the Syrian-Arabian Plateau. In historical times eruptions also occurred in the

interior of the continent in the Xiao Hinggan Range and the Anyuy highlands.

It is common practice in geographic literature to divide Asia into large regions, each grouping

together a number of countries. Those physiographic divisions usually consist of North Asia,

including the bulk of Siberia and the northeastern edges of the continent; East Asia, including the

continental part of the Russian Far East region of Siberia, the East Asian islands, Korea, and

eastern and northeastern China; Central Asia, including the Plateau of Tibet, the Junggar and Tarim

basins, the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of China, the Gobi, and the Sino-Tibetan ranges; Middle

Asia, including the Turan Plain, the Pamirs, the Gissar and Alay ranges, and the Tien Shan; South

Asia, including the Philippine and Malay archipelagoes, peninsular Southeast Asia and peninsular

India, the Indo-Gangetic Plain, and the Himalayas; and West (or Southwest) Asia, including the West

Asian highlands (Anatolia, Armenia, and Iran), the Levant, and the Arabian Peninsula. Sometimes the

Philippines, the Malay Archipelago, and peninsular Southeast Asia, instead of being considered part

of South Asia, are grouped separately as Southeast Asia. Yet another variation of the basic

categories is commonly made to divide Asia into its cultural regions.

Northeastern Siberia comprises faulted and folded mountains of moderate height, such as the

Verkhoyansk,

Chersky, and Okhotsk-Chaun mountain arcs, all Mesozoic structures that have been rejuvenated by

geologically recent tectonic events. The Koryak Mountains are similar but have a Cenozoic origin.

Volcanic activity took place in those areas during the Cenozoic. Some plateaus are found in the

areas of

the ancient massifs, such as the Kolyma Mountains. Traces of several former centres of mountain

glaciers

remain, as well as traces of lowland originally covered by the sea, such as the New Siberian

Islands.

The Prilenskoye and Aldan plateaus—comprising an ancient peneplain resting on the underlying

platform

that sometimes outcrops on the surface—are located in the region. Traces of ancient glaciation also

can

be distinguished.The dominant feature of north-central Siberia is the Central Siberian Plateau, a

series of plateaus and stratified plains that were uplifted in the Cenozoic. They are composed of

terraced and dissected mesas with exposed horizontal volcanic intrusions, plains formed from

uplifted Precambrian blocks, and a young uplifted mesa, dissected at the edges and partly covered

with traprock (Putoran Mountains). On the eastern periphery is the Central Yakut Lowland, the

drainage basin of the lower Lena River, and on the northern periphery is the North Siberian Lowland,

covered with its original marine deposits.The West Siberian Plain is stratified and is composed of

Cenozoic sediments deposited over thicknesses of Mesozoic material, in addition to folded bedrock.

The northern part was subjected to several periods of glaciation throughout the Quaternary Period

(the past 2.6 million years). In the south, glaciofluvial and fluvial deposits predominate.In the

northern part of the region are the mountains and islands of the Asian Arctic. The archipelago of

Severnaya Zemlya is formed of fragments of fractured Paleozoic folded structures. Throughout the

region there has been vigorous contemporary glaciation.

The main features in the northern region of East Asia include the Da Hinggan, Xiao Hinggan, and

Bureya ranges; the Zeya-Bureya Depression and the Sikhote-Alin ranges; the lowlands of the Amur and

Sungari rivers and Lake Khanka; the Manchurian-Korean highlands running along North Korea’s border

with China; the ranges extending along the eastern side of the Korean peninsula; the Northeast

(Manchurian) Plain; the lowlands of the Liao River basin; and the North China Plain. Most of those

features were formed by folding, faulting, or broad zonal subsidence. The mountains are separated by

alluvial lowlands in areas where recent subsidence has occurred.The mountains of southeastern China

were formed from Precambrian and Paleozoic remnants of the Yangtze paraplatform by folding and

faulting that occurred during the Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras. The mountain ranges are numerous, are

of low or moderate elevation, and occupy most of the surface area, leaving only small, irregularly

shaped plains.The islands off the coast of East Asia and the Kamchatka Peninsula are related

formations. The Ryukyu Islands, Japan, Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands are uplifted fragments of the

Ryukyu-Korean, Honshu-Sakhalin, and Kuril-Kamchatka mountain-island arcs. Dating from the Mesozoic

and Cenozoic eras, those arcs have complex knots at their junctions, represented by the topography

of the Japanese islands of Kyushu and Hokkaido. The mountains are of low or moderate height and are

formed of folded and faulted blocks; some volcanic mountains and small alluvial lowlands also are to

be found.Kamchatka is a mountainous peninsula formed from fragments of the Kamchatka-Koryak and

Kuril-Kamchatka arcs, which occur in parallel ranges. The geologically young folds enclose rigid

ancient structures. Cenozoic (including contemporary) volcanism is pronounced, and the peninsula has

numerous geysers and hot springs. Vast plains exist that are composed of alluviums and volcanic

ashes.

Central Asia consists of mountains, plateaus, and tablelands formed from fragments of the ancient

platforms and surrounded by a folded area formed in the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras. The mountains

of southern Siberia and Mongolia were formed by renewed uplift of old faulted and folded blocks;

ranges are separated by intermontane troughs. The Alpine mountains—the Altai, Sayan, and Stanovoy

mountains—are particularly noticeable. They have clearly defined features resulting from ancient

glaciation; contemporary glaciers exist in the Altai.The Central Asian plains and tablelands include

the Junggar Basin, the Takla Makan Desert, the Gobi, and the Ordos Desert. Relief features vary from

surfaces leveled by erosion in the Mesozoic and Cenozoic to plateaus with low mountains, eroded

plateaus on which loess had accumulated, and vast sandy deserts covered with wind-borne alluvium and

lacustrine deposits.Alpine Asia—sometimes known as High Asia—includes the Pamirs and the eastern

Hindu Kush, the Kunlun Mountains, the Tien Shan, the Gissar and Alay ranges, the Plateau of Tibet,

the Karakoram Range, and the Himalayas. The Pamirs and the eastern Hindu Kush are sharply uplifted

mountains dissected into ridges and gorges in the west. The Kunlun Mountains, the Tien Shan, and the

Gissar and Alay ranges belong to an alpine region that was formed from folded structures of

Paleozoic age. Glaciers are present throughout the region but are most concentrated at the western

end of the Himalayas and in the Karakoram Range.The Plateau of Tibet represents a fractured alpine

zone in which Mesozoic and Cenozoic structures that surround an older central mass have experienced

more recent uplifting. Some of the highlands are covered with sandy and rocky desert; elsewhere in

that region, alpine highlands are dissected by erosion or are covered with glaciers. The Karakoram

Range and the Himalayas were uplifted during late Cenozoic times. Their erosion has exposed older

rocks that were deformed during earlier tectonic events.

South Asia, in the limited sense of the term, consists of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, peninsular India,

and Sri Lanka. The Indo-Gangetic Plain is formed from the combined alluvial plains of the Indus,

Ganges (Ganga), and Brahmaputra rivers, which lie in a deep marginal depression running north of and

parallel to the main range of the Himalayas. It is an area of subsidence into which thick

accumulations of earlier marine sediments and later continental deposits have washed down from the

rising mountains. The sediments provide fertile soil in the Ganges and Brahmaputra basins and in

irrigated parts of the Indus basin, while the margins of the Indus basin have become sandy deserts.

Peninsular India and Sri Lanka are formed of platform plateaus and tablelands, including the vast

Deccan plateau, uplifted in the Mesozoic and Cenozoic. The region includes tablelands with uplifted

margins, such as the Western and Eastern Ghats, and terraced and dissected plateaus with lava

mantles or intrusions.

Southeast Asia is composed of peninsular Southeast Asia and the islands and peninsulas to the

southeast of the Asian continent. The mainland consists of the western mountain area and the central

and eastern mountains and plains. The western mountain area of Myanmar (Burma) is a fold belt of

Cenozoic age. Mountains of medium elevation constitute folded blocks that decrease in size and

elevation to the south; the valleys are alluvial and broaden out to the south. Central and eastern

Thailand and central and southern Vietnam are characterized by mountains of low and moderate height

that have been moderately fractured. The region is one of Mesozoic structures surrounding the

ancient mass known as the Kontum block, which comprises plateaus and lowlands filled with

accumulated alluvial deposits.Archipelagoes border the southeastern margin of Asia, consisting

mainly of island arcs bordered by deep oceanic trenches. The Indian Ocean arcs—Sumatra, Java, and

the Lesser Sunda Islands—consist of fragments of Alpine folds that constitute a complex assemblage

of rock types of different ages. Vigorous Cenozoic volcanic activity, continuing up to the present,

has formed volcanic mountains, and their steady erosion has filled the adjacent alluvial lowlands

with sediment.Borneo and the Malay Peninsula are formed from fractured continental land situated at

the junction of the Alpine-Himalayan and East Asiatic downwarp regions. The mountains are composed

of folded and faulted blocks; the lowlands are alluvial.The Pacific Ocean island arcs, including

Celebes (Sulawesi), the Moluccas (Maluku), the Philippine Islands, and Taiwan, have been built by

ongoing tectonic processes, particularly volcanism. Mountain areas of moderate height, volcanic

ranges, alluvial lowlands, and coral reef islets are present throughout those regions.

Middle Asia includes the plains and hills lying between the Caspian Sea to the west and Lake

Balkhash to the east. That area is composed of flat plains on continental platforms of folded

Paleozoic and Mesozoic bedrock. Individual uplifted portions form low, rounded hills in the Kazakh

region, low mountains on the Tupqaraghan and Türkmenbashy (Krasnovodsk) peninsulas of the Caspian

Sea, and mesas (isolated hills with level summits and steeply sloping sides) in areas of earlier

marine sedimentation, such as the Ustyurt Plateau and the Karakum Desert. Thick accumulations of

alluvium have been transported by the wind, forming sandy deserts in the south. Original marine and

lacustrine sediments adjoin the shores of the Caspian and Aral seas and Lake Balkhash.

West Asia includes the highlands of Anatolia, the Caucasus, and the Armenian and Iranian

highlands.The highlands of Anatolia—the Pontic Mountains that parallel the Black Sea, and the Taurus

and Anatolian tablelands—are areas of severe fragmentation, heightened erosional dissection, and

isolated occurrences of volcanism. The Greater Caucasus Mountains are a series of upfolded ranges

generally running northwest to southeast between the Black and Caspian seas. The Armenian Highland

is a region of discontinuous mountains including the Lesser Caucasus and the Kurt mountains.

Geologically recent uplifting, in the form of a knot of mountain arcs, took place during a period of

vigorous volcanism during the Cenozoic. The region is seismically active and is known for its

destructive earthquakes.The Iranian highlands comprise mountain arcs (the Elburz, the Kopet-Dag, the

mountains of Khorāsān, the Safīd Range, and the western Hindu Kush in the north; the Zagros, Makrān,

Soleymān, and Kīrthar mountains in the south), together with the plateaus of the interior and the

central Iranian, eastern Iranian, and central Afghanistan mountains. There are isolated volcanoes of

Cenozoic origin, a predominance of accumulated remnants resulting from ancient erosion, and saline

and sandy deserts in the depressions and stony deserts (hammadas) on the tablelands.

Southwest Asia, like much of southern Asia, is made up of an ancient platform—the northern fragments

of Gondwanaland—in which sloping plains occur in the marginal downwarps. Its principal components

are the Arabian Peninsula and Mesopotamia.The Arabian Peninsula is a tilted platform, highest along

the Red Sea, on which the stratified plains have undergone erosion under arid conditions. Plateaus

with uplifted margins, Cenozoic lava plateaus, stratified plains, and cuestas (long, low ridges with

a steep face on one side and a long, gentle slope on the other) all occur. Ancient marine sands and

alluvium, resulting from previous subsidence and sedimentation, now take the form of vast sandy

deserts.Mesopotamia consists of the Tigris and Euphrates floodplains and of the deltas from Baghdad

to the Persian Gulf. The original lowland is covered with late Cenozoic sedimentation; the elevated

plain, on the other hand, has been dissected by erosion and denudation under the continental

conditions prevailing in the late Cenozoic.

Asia is a land of great rivers. The Ob, Irtysh, Yenisey with the Angara, Lena (with the waters of

the Aldan and the Vilyuy), Yana, Indigirka, and Kolyma rivers all flow northward into the Arctic

Ocean. Among rivers draining into the Pacific Ocean are the Anadyr, Amur (combined with the Sungari

[Songhua] and the Ussuri rivers), Huang He (Yellow River), Yangtze (Chang), Xi, Red, Mekong, and

Chao Phraya.The Salween, Irrawaddy, Brahmaputra, Ganges (Ganga), Godavari, Krishna, and Indus rivers

flow into

the Indian Ocean, as does the Shatt al-Arab, which is the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates

rivers. The Kura and Aras rivers flow into the Caspian Sea. Only small mountain rivers flow from

Asia into the Sea of Azov, the Black Sea, and the Mediterranean Sea. The Amu Darya (ancient Oxus

River), Syr Darya (ancient Jaxartes River), Ili (Yili), Tarim, Helmand, and Harīrūd (Tejen) rivers

empty into vast interior basins. Some of those rivers end in lakes; others end in deltas in the

sands or salt marshes; and still others flow into oases, where all the water is used to irrigate

fields or else evaporates.All of the Siberian rivers freeze over in the winter, and some freeze to

the bottom. In spring widespread flooding occurs as snow fields melt. Those rivers are important

communication routes, being used by watercraft during the summer and as roads for sleighs and

snowmobiles in winter; they also teem with fish.In the dry regions where drainage is landlocked,

many large rivers are temporary ones fed by melting snow and glaciers in the mountains; they reach

their peak water levels in summer. Rivers in dry regions that are not fed by mountain runoff have

little water; their levels vary sharply, and periodically or occasionally they dry up completely.

The rivers of the monsoon climate regions reach their maximum volume in summer and are utilized for

irrigation. The Asian rivers in the vicinity of the Mediterranean that are not fed by mountain snows

grow shallow in summer and sometimes even dry up. In the tropical regions, however, the rivers

perennially are full of water.

The many lakes of Asia vary considerably in size and origin. The largest of them—the Caspian and

Aral seas—are the remains of larger seas. The Caspian has been fluctuating in size, and the Aral has

been shrinking, primarily because its tributaries, the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, have been tapped

heavily for irrigation purposes. Lakes Baikal, Ysyk-Köl, and Hövsgöl (Khubsugul), the Dead Sea, and

others lie in tectonic depressions. The basins of Lakes Van, Sevan, and Urmia are, furthermore,

encircled by lava, and Lake Telets was gouged out by ancient glaciation. A number of lakes were

formed as the result of landslides (Lake Sarez in the Pamirs), karst processes (the lakes of the

western Taurus, in Turkey), or the formation of lava dams (Lake Jingpo in northeastern China and

several lakes in the Kuril Islands). In the volcanic regions of the eastern Asian islands, in the

Philippines, and in the Malay Archipelago, lakes have formed in craters and calderas. The subarctic

has a particularly large number of lakes; in addition to lakes formed as a result of melting

permafrost and subsidence, there are also ancient glacial moraine lakes. Many lagoonal lakes occur

along low coastlines.The lakes in the internal drainage basins—such as Koko Nor, Lake Tuz, and

others—are usually saline. Lake Balkhash has fresh water in the west and brackish water in the east.

Lakes through which rivers flow are freshwater and regulate the flow of the rivers that issue from

them or flow into them; notable examples are Lake Baikal, associated with the Angara River; Lake

Khanka (the Song’acha and Ussuri rivers); Dongting Lake and Lake Poyang (the Yangtze River); and

Tonle Sap (the Mekong). Large reservoirs have also been created by constructing hydroelectric

stations.

In arid regions groundwater (subterranean water) is often the only source of water. Large

accumulations are known to exist in artesian basins and beneath the dipping plains at the foot of

mountains; those basins are associated with the extensive oases of Central Asia, Kashgaria, and many

other regions.

The soils of Asia are marked by the combined effects of climate, topography, hydrology, plant and

animal life, age, and economic activities. All of those factors vary considerably from one part of

that vast continent to another, from north to south, and from lower to higher elevations in

mountainous regions. The soil also shows a horizontal zonality that is especially clearly defined in

the continental plains.

In the Arctic, where glacial and Arctic deserts predominate, the processes of soil building occur

only in rudimentary form. The soils are skeletal and low in humus. The subarctic north of Asia is

occupied by a timberless zone of tundra vegetation. The subarctic climate and tundra vegetation give

rise to specifically tundra-type soils, which are characterized by poor drainage (due to permafrost)

and only a short period in which it is possible for organic substances to decompose. Those

conditions result in the accumulation of undecomposed organic residues in the form of particles of

peat. The poor drainage creates an oxygen-free medium in which a bluish substance known as gley is

formed. Thus, peaty-gley soils are most characteristic of the tundra. There are widespread

occurrences of movement by solifluction (or mudflows), heaving of the ground because of frost,

settling or caving in of the ground from thawing, and formation of stone rings around central areas

of debris in regions covered with boulders.

Farther south stretches the transitional belt of the forest tundra, where tundra and sparse forest

alternate with regularity. Tundra soils alternate with the soils of the taiga (boreal forest), the

cold, swampy forested region. The soils below the frozen taiga are called cryogenic (influenced by

frost action). In the mountainous regions the peaty-gley soils are replaced by mountain tundra and

weakly developed, often embryonic soils of detritus and stony fragments.

The forest zone occupies the largest part of the temperate zone. Characteristic of soil formation in

the forest zone is the leaching process. The forest leaves and needles that fall, together with dead

remains of the sparse grass cover, are subjected to decomposition by organic acids in the litter of

the forest floor. The duration of the summer season and the amount of precipitation are sufficient

for complete decomposition of the soluble soil components, and the soil solutions transport them and

leach them into deeper soil horizons (layers). The undecomposed quartz grains remain in the upper

horizon, which is therefore infertile; that layer resembles light-gray ashes, which is the reason

soils of that type are called podzols (Russian: “under ashes”). Different degrees of leaching occur

in the various subzones of the forest zone. A dense rusty brown horizon of wash-down (deposition in

an underlying layer of soil) underlies the podzolic portion of the soil profile (or layer); its

colour is related to the accumulation of iron and aluminum oxides. That layer, called orstein, or

iron pan, is impervious to water and contributes to the self-swamping of the taiga forests. East of

the Yenisey River, where permafrost occurs across the entire breadth of the forest zone, soil

drainage (and consequently the leaching process) is made more difficult, and the typical podzols are

therefore replaced by specific cryogenic taiga soils. Marshes and bog-type soils are widely

distributed over a considerable part of the taiga subzones.The deciduous forest subzones of Asia

form two distinct areas. In western Siberia there are small-leafed (primarily birch or aspen)

forests on gray forest soils. They are more gray in colour than the podzols because of the greater

amount of organic substances—such as tree leaves and a more abundant grass cover—feeding those

soils. That explains their higher humus content, as well as their greater fertility. The second

section of the deciduous forest subzone has survived in East Asia, stretching from the Xiao Hinggan

Range in the west to the Japanese island of Honshu in the east; in that subzone abundant warmth and

moisture intensify chemical weathering, and iron oxides accumulate even in the surface soil

horizons. In that manner brown forest soils, known as forest burozems, are formed.

Soil cover in the forest-steppe region is formed when the ratio of precipitation to evaporation is

in equilibrium and as the leaching process of the wet season alternates with the upward flow of the

soil solutions during the dry period. Under those conditions, with organic material resulting from

the dense vegetation abundantly available, humus accumulation in the soil is considerable, and

dark-coloured soils are formed that are the most fertile in all Asia; known as chernozems, they are

the thickest of the forest-steppe and mixed-grass soils. Characteristic of the wooded-meadow plains

of the Amur River basin (the “Amur prairies”) are meadow soils that are dark, moist, and often

composed of blue gley. In the drier steppes, where vegetation is sparse, the amount of humus is

reduced and the content of unleached mineral salts is increased; transport of the dissolved salts to

the surface by the upward flow of soil solutions is also intensified. Associated with that process

is a bleaching and salinization of the soil. The drier steppes thus form a transitional zone from

the shallow southern chernozems to the chestnut soils. Broad expanses of the forest-steppe and

steppe are under cultivation and serve as rich granaries. Severe wind erosion occurs during the hot,

dry seasons. In many areas surface washout and gully erosion have also impoverished the soil,

despite preventive efforts.

Through inner Kazakhstan and Mongolia stretches a zone of semidesert, and in Middle Asia, the

Junggar (Dzungarian) Basin, the Takla Makan Desert, and Inner Mongolia, there is a belt of

temperate-zone deserts. A belt of subtropical deserts extends through the Levant, the Iranian

highlands, and the southern edge of Middle Asia. Beneath the semideserts, with their mosaic of

desert and arid-steppe vegetation, light chestnut and light brown semidesert soils form; those are

low in humus but contain an abundance of strongly alkaline soil. Beneath the deserts, where the

supply of organic substances, as well as the humus content, is extremely low, gray-brown soils form

in the temperate zone, while gray desert soils (sierozems) develop in the arid subtropics. A great

deal of saline soil is present there, and agriculture is possible only with the use of irrigation,

which gives rise to specific cultivated types of sierozems.Only in western Asia is the tropical

desert zone clearly defined. Broad expanses of that area are characterized by embryonic soils and

desert crusts, as well as by blowing sands.

In the maritime areas of the Asiatic Mediterranean—Anatolia and the Levant—xerophytic vegetation

(vegetation structurally adapted to exist with very little water) of the Mediterranean

scrub-woodland types, known as maquis (evergreen), shiblyak (deciduous), and frigana (low-growing

thorny, cushionlike bushes), is prevalent. The predominant soils under such vegetation are brown;

they have accumulated iron as a result of the intense chemical weathering during the wet

Mediterranean winter and of the upward flow of soil solutions during the dry summer. Frigana

vegetation is widely represented in the West Asian semidesert highlands. Here soils have developed

that are transitional between the brown soils and the sierozems.

Typical of Asia’s monsoonal subtropics are soils that formed beneath the evergreen forests that once

occupied the southern portion of the Korean peninsula, southwestern Japan, and southeastern China.

Intensive chemical weathering during the warm and wet summer monsoon season results—as it also does

in the more southerly torrid zones—in the decomposition and leaching of many soil minerals, the

accumulation of residual iron and aluminum oxides, and the consequent predominance of red and yellow

soils as well as of podzolized soils. Agriculture is especially widespread on the alluvial soils of

the plains and on terraced slopes in hilly terrain, in both cases dominated by irrigated paddy-rice

cultivation.

Savannas (grassy parklands) and dry-tropical deciduous forests predominate in the rain shadow on the

leeward slopes of hills, and wet-tropical evergreen forests grow on the rainy windward slopes of

hills. Intensive leaching followed by evaporation is characteristic of those soils. Under the

wet-tropical forests, red-yellow laterites (leached and hardened iron-bearing soils) predominate;

beneath the savannas and dry-tropical forests, there are red lateritic soils that change, with

increasing aridity, to red-brown and desert brown soils. Beneath the dry savannas of peninsular

India are unique black soils called regurs that are thought to develop from basalt rock.In the

equatorial zone (southern Malaysia and the Greater Sunda Islands), typical tropical rainforests have

developed. In southwestern Sri Lanka and on the Indonesian island of Java, they have been almost

entirely replaced by an agricultural landscape in which mountain slopes and hills are covered with

plantations of tea, coconut palms, and rubber trees. The soils are lateritic and are red-yellow or

brick-red, with marginal degrees of laterization.In the valleys of the subequatorial and equatorial

zones, alluvial soils predominate; they have been developed by thousands of years of cultivation and

irrigation of the rice fields. Artificial terracing of the slopes is practiced on a large scale in

the mountainous regions, both for purposes of irrigation and to prevent soil erosion.

In the mountains zones of different soil types are found at different elevations. As a rule they are

skeletal, underdeveloped soils, clearly reflecting the differences in rock structure and origin and

in the degree of exposure of the slopes. The boundaries of the vertical zones become higher from

north to south, and the number of zones increases. Mountain soils also correspond to the different

vegetation zones that occur at different elevations.The vertical soil zones correlate with the

landscape zones as elevation increases. A zone of forest, followed higher up by meadows and with

snow cover at the highest altitudes, is characteristic of the western maritime regions. On lower

slopes in the western Caucasus, for example, broad-leaved mountain forests occur on brown

mountain-forest soils; above those are coniferous forests on mountain podzolic soils, followed by

stunted trees, followed in turn by subalpine and alpine meadows on mountain-meadow soils, while the

highest ridges are covered in perennial snow and glaciers. Associations of desert, steppe,

meadowland, and snow zones are widespread in the interior of Asia and sometimes include

mountain-forest zones. Characteristic of the Tien Shan, for example, is the predominance of

mountain-desert and semidesert landscapes, which occur in association with gray-brown and brown

mountain soils in the foothills of the ranges, while higher up are mountain steppes associated with

mountain chestnut soils and mountain chernozems. Under parts of the mountain forest-steppe and the

mountain forests, the soils are podzolized.Typical of the mountains of eastern Siberia are the

taiga-tundra spectra that occur in vertical zones. Thus, mountain taiga on taiga-cryogenic soils is

followed by a zone of dwarfed trees, then by mountain tundra, and finally by bald peaks.In eastern

Asia the subalpine and alpine meadow zones with mountain-meadow soils sometimes disappear; instead,

mountain-forest landscape extends as far up in elevation as the vicinity of the crests and is

succeeded only by a zone of stunted trees and shrubs. The spectra of the alpine regions of South

Asia (notably the Himalayas) are distinguished by the most complex variety of vegetation and soil

types.

Virgin soils have been greatly transformed in the areas where agriculture has long been practiced.

Sometimes primary soils are buried under a thick cultivated layer that is high in humus, nitrogen,

phosphorus, and trace elements. The irrigated soils of valleys and deltas of the Murgab (Middle

Asia), the Tigris and Euphrates, and the Indus rivers have a layer of agricultural deposits 10 to 15

feet (3 to 5 metres) thick. The “black-land” (heitu) soils of the Loess Plateau in China consist of

a fertile layer 1 to 3 feet (30 to 90 cm) thick of organic material accumulated by local farmers.

Rice cultivation in the monsoonal regions of Asia has a particular impact on primary-soil cover. The

upper layer of those so-called “rice soils” is degraded as a result of regular flooding and is

subject to the gleying process. The basic properties of those soils remain constant for centuries,

but the soils do not exhibit high fertility.The most harmful and extended phenomenon among the

effects of irrigation on soil cover in Asia is that of secondary salinization. That process, which

is a result of improper agricultural practices, is widespread in the soils of the arid, semiarid,

and subhumid zones of Asia that are irrigated without appropriate drainage. Salt-affected soils

account for large areas in Central Asia, South Asia, and Southwest Asia.Soil degradation from

erosion has also hurt agricultural production. The areas of most significant erosion have occurred

in the Ganges (Ganga) River basin, the lower elevations of the Himalayas, the Huang He basin, and

the Loess Plateau. Severe soil erosion has resulted from year-round cultivation of the plains and

from deforestation of water-catchment areas in the mountains.

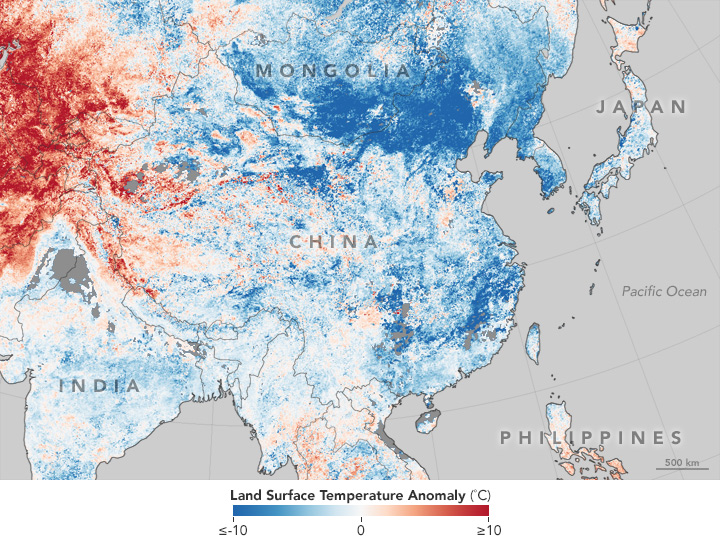

The enormous expanse of Asia and its abundance of mountain barriers and inland depressions have

resulted in great differences between regions in solar radiation, atmospheric circulation,

precipitation, and climate as a whole. A continental climate, associated with large landmasses and

characterized by an extreme annual range of temperature, prevails over a large part of Asia. Air

reaching Asia from the Atlantic Ocean, after passing over Europe or Africa, has had time to be

transformed into continental air—i.e., air that has often lost much of the moisture it absorbed over

the ocean. As a result of the prevalent eastward movement of the air masses in the midlatitudes, as

well as the isolating effect of the marginal mountain ranges, the influence of sea air from the

Pacific Ocean extends only to the eastern margins of Asia. From the north, Arctic air has unimpeded

access into the continent. In the south, tropical and equatorial air masses predominate, but their

penetration to the centre of Asia is restricted by the ridges of the moutainous belt stretching from

the highlands of West Asia through the Himalayas to the mountains of southern China and Southeast

Asia; in the winter months (November through March), such penetration is further impeded by the

density of the cold air masses over the interior.The contrast between the strong heating of the

continent in the summer months (May to September) and the chilling in winter produces sharp seasonal

variations in atmospheric circulation and also enhances the role of local centres of atmospheric

activity. Winter chilling of the Asian landmass develops a persistent high-pressure winter

anticyclone over Siberia, Mongolia, and the Plateau of Tibet that is normally centred southwest of

Lake Baikal. The area affected by the anticyclone is characterized by temperature inversions and by

very cold, calm weather with little snowfall. The winter anticyclone is fed by subsiding upper air,

by bursts of Arctic air flowing in from the north, and by the persistent westerly air drift that

accompanies the gusty cyclonic low-pressure cells operating within the Northern Hemisphere cyclonic

storm system. The high pressure propels cold, dry air eastward and southward out of the continent,

affecting eastern and southern Asia during the winter. Only a few of the winter cyclonic lows moving

eastward out of Europe carry clear across Asia, but they do bring more frequent changes in weather

in western Siberia than in central Siberia. The zone of lowest temperature—a so-called cold pole—is

found in the northeast, near Verkhoyansk and Oymyakon, where temperatures as low as −90 °F (−68 °C)

and −96 °F (−71 °C), respectively, have been recorded.The outward drift of winter air creates a

sharp temperature anomaly in eastern and northeastern Asia, where the climate is colder than the

characteristic global average for each given latitude. On the East Asian islands, the effect of the

winter continental monsoon is tempered by the surrounding seas. As the air masses pass over the

seas, they become warmed and saturated with moisture, which then falls as either snow or rain on the

northwestern slopes of the island arcs. Occasionally, however, strong bursts of cold air carry cold

spells as far south as Hong Kong and Manila.

Cyclonic storms form and move eastward through the zone where the temperate and tropical air masses

are in contact, called the polar front, which shifts southward in winter. The winter rainy season in

the southern parts of the West Asian highlands, which is characteristic of the Mediterranean

climate, is associated with that southward movement of the polar front. In northern areas of West

and Middle Asia, the effect of cyclonic action is particularly strong in the spring, when the polar

front moves north and causes the maximum in annual precipitation to occur then.During the northern

winter, South and Southeast Asia are affected by northeasterly winds that blow from high-pressure

areas of the North Pacific Ocean to the equatorial low-pressure zone. Those winds are analogous to

the trade winds and are known in South Asia as the northeast (or winter) monsoon. The weather is dry

and moderately warm. Rainfall occurs only on the windward side of maritime regions (e.g., Tamil Nadu

state in southeastern India and southern Vietnam). Some of the cyclonic storms that move eastward

through the Mediterranean Basin during the winter are deflected south of the Plateau of Tibet,

crossing northern India and southwestern China. Such storms do not often bring winter rain, but they

create short periods of cloudy, cool, or gusty weather and are accompanied by snow in the higher

mountain ranges.In summer the polar front shifts northward, causing cyclonic rains in the mountains

of Siberia. In West, Middle, and Central Asia, a hot, dry, dusty, continental tropical wind blows at

that time. Over the basin of the Indus River, the heating creates a low-pressure area. Known as the

South Asian (or Iranian) low, it appears in April and is fully developed from June to August. The

onset of monsoon in India and mainland Southeast Asia is related to changes in the circulation

pattern that occur by June—specifically, the disintegration of the southern jet stream and the

formation of low pressure over southern Asia. The monsoon air masses flow into that monsoonal

low-pressure zone from a cell of high pressure just off the eastern coast of southern Africa.

Because of the Coriolis force (the force caused by the Earth’s rotation), winds south of the Equator

change direction from southeast to southwest in the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal. The southwest

monsoon bursts upon the Malabar Coast of southwestern India in early June and gradually extends

northward over most of the Indian subcontinent and mainland Southeast Asia. It brings considerable

rainfall, which in most of those areas accounts for 80 to 90 percent of the total annual

precipitation.In eastern Asia the Pacific Ocean polar front creates atmospheric disturbances during

the summer. From a summer high-pressure centre over the western Pacific, the warm and moist summer

monsoon blows from the southeast toward the continent. To the south of latitude 38° N, where the

warm Kuroshio (Japan Current) approaches the coast of Japan, the summer monsoon brings protracted

rains and high humidity; together with high temperatures, that creates a hothouse atmosphere.

Becoming chilled as it passes over cold ocean currents to the north, that air brings fogs and

drizzling rains to northeastern Asia.

Summer in China is a time of variable air movement out of the western Pacific. If that drift is

strong and low pressure over the continental interior is intense, the summer monsoon may carry

moisture well into Mongolia. If neither the drift nor the continental low is strong, the China

summer monsoon may fail, falter over eastern China, or cause irregular weather patterns that

threaten the country with crop failure. The monsoon there is less dramatic than in other areas,

accounting for 50 to 60 percent of China’s annual rainfall.Tropical cyclones—called typhoons in the

Pacific Ocean—may occur in coastal and insular South, Southeast, and East Asia throughout the year

but are most severe during the late summer and early autumn. Those storms are accompanied by strong

winds and torrential rains so heavy that the maximum precipitation from the typhoons locally may

exceed the total amounts received during the normal summer monsoons.In winter continental tropical

air prevails in tropical Asia; in summer it is replaced by equatorial ocean air. The winter season’s

dry and warm winds, directed offshore toward the equatorial low-pressure axis, are analogous to

trade winds but simultaneously act as the South Asian continental monsoon. The dry spring that

follows changes abruptly and dramatically into the rainy summer with the onset of the monsoon. The

summer monsoon brings enormous amounts of rain (up to about 25 inches [635 mm] in a month). Over the

areas of Asia closest to the Equator—southern Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and the Greater Sunda

Islands—equatorial air prevails continuously, accompanied by even temperatures and abundant rainfall

in all seasons. The Lesser Sunda Islands have a tropical monsoon climate; their wet and dry seasons

are regulated by the calendar rhythm of the Southern Hemisphere, which is characterized by a wet

summer from November to February and a dry winter from June to October.

Differences between the climatic conditions of the various regions of Asia are determined to a

considerable degree by topography. Different elevation-based climatic zones are most clearly defined

on the southern slopes of the Himalayas, where they vary from the tropical climates of the

foothills, at the lowest levels, to the extreme Arctic-like conditions of the peaks, at the highest

elevations. The degree of exposure also plays a large role. The sunny southern slopes differ from

the shady northern ones, and windward slopes exposed to moist ocean winds differ from leeward

slopes, which, lying in the wind (and rain) shadow, are necessarily drier. The barrier effect is

most pronounced in the zone of monsoon circulation (i.e., East, Southeast, and South Asia), where

rain-bearing winds have a constant direction. In addition to the physical isolation of the leeward

slopes from the moisture-laden winds, those slopes also experience the foehn effect, in which a

strong wind traverses a mountain range and is deflected downward as a warm, dry, gusty, erratic

wind. Contrasts of climate resulting from exposure are manifested clearly in the Himalayas, the

Elburz Mountains, Japan, Taiwan, the Philippines, the Tien Shan range, the region to the east of

Lake Baikal (Transbaikalia), and many other places.The isolating barrier effect of the relief on the

climate is demonstrated most clearly in the West Asian highlands and in Central Asia. In those

regions the surrounding mountains isolate the tablelands of the interior from moisture-laden winds.

The massiveness of the interior highlands is also a significant factor; it gives rise to local

anticyclones during the cold months of the year.

Botanists nickname China the “Mother of Gardens.” It has more flowering plant species than North and South

America combined. Because China has such diverse landscapes, from the arid Gobi Desert to the tropical rain

forests of Yunnan Province, many flowers can adapt to climates all over the world. From roses to peonies,

many familiar flowers most likely originated in northern China. China is the likely origin of such fruit

trees as peaches and oranges. China is also home to the dawn redwood, the only redwood tree found outside

North America.

Asia’s diverse physical and cultural landscape has dictated the way animals have been domesticated. In the

Himalayas, communities use yaks as beasts of burden. Yaks are large animals related to cattle, but with a

thick fiber coat and the ability to survive in the oxygen-poor high altitude of the mountains. Yaks are not

only used for transportation and for pulling plows, but their coats are sources of warm, hardy fiber. Yak

milk is used for butter and cheese.

In the Mongolian steppe, the two-humped Bactrian camel is the traditional beast of burden. Bactrian camels

are critically endangered in the wild. The camel’s humps store nutrient-rich fat, which the animal can use

in times of drought, heat, or frost. Its size and ability to adapt to hardship make it an ideal pack animal.

Bactrians can actually outrun horses over long distances. These camels were the traditional animals used in

caravans on the Silk Road, the legendary trade route linking eastern Asia with India and the Middle East.

The freshwater and marine habitats of Asia offer incredible biodiversity.

Lake Baikal’s age and isolation make it a unique biological site. Aquatic life has been able to evolve for

millions of years relatively undisturbed, producing a rich variety of flora and fauna. The lake is known as

the “Galápagos of Russia” because of its importance to the study of evolutionary science. It has 1,340

species of animals and 570 species of plants.

Hundreds of Lake Baikal’s species are endemic, meaning they are found nowhere else on Earth. The Baikal

seal, for instance, is one of the few freshwater seal species in the world. The Baikal seal feeds primarily

on the Baikal oil fish and the omul. Both fishes are similar to salmon, and provide fisheries for the

communities on the lake.

The Bay of Bengal, on the Indian Ocean, is one of the world’s largest tropical marine ecosystems. The bay is

home to dozens of marine mammals, including the bottlenose dolphin, spinner dolphin, spotted dolphin, and

Bryde’s whale. The bay also supports healthy tuna, jack, and marlin fisheries.

Some of the bay’s most diverse array of organisms exist along its coasts and wetlands. Many wildlife

reserves in and around the bay aim to protect its biological diversity.

The Sundarbans is a wetland area that forms at the delta of the Ganges and Brahamaputra rivers. The

Sundarbans is a huge mangrove forest. Mangroves are hardy trees that are able to withstand the powerful,

salty tides of the Bay of Bengal as well as the freshwater flows from the Ganges and Brahamaputra. In

addition to mangroves, the Sundarbans is forested by palm trees and swamp grasses.

The swampy jungle of the Sundarbans supports a rich animal community. Hundreds of species of fish, shrimp,

crabs, and snails live in the exposed root system of the mangrove trees. The Sundarbans supports more than

200 species of aquatic and wading birds. These small animals are part of a food web that includes wild boar,

macaque monkeys, monitor lizards, and a healthy population of Bengal tigers.

Made from ❤️ by Divyesh Idhate