Europe, second smallest of the world’s continents, composed of the westward-projecting peninsulas of Eurasia (the great landmass that it shares with Asia) and occupying nearly one-fifteenth of the world’s total land area. It is bordered on the north by the Arctic Ocean, on the west by the Atlantic Ocean, and on the south (west to east) by the Mediterranean Sea, the Black Sea, the Kuma-Manych Depression, and the Caspian Sea. The continent’s eastern boundary (north to south) runs along the Ural Mountains and then roughly southwest along the Emba (Zhem) River, terminating at the northern Caspian coast.

Europe’s largest islands and archipelagoes include Novaya Zemlya, Franz Josef Land, Svalbard, Iceland, the

Faroe Islands, the British Isles, the Balearic Islands, Corsica, Sardinia, Sicily, Malta, Crete, and Cyprus.

Its major peninsulas include Jutland and the Scandinavian, Iberian, Italian, and Balkan peninsulas. Indented

by numerous bays, fjords, and seas, continental Europe’s highly irregular coastline is about 24,000 miles

(38,000 km) long.

Among the continents, Europe is an anomaly. Larger only than Australia, it is a small appendage of Eurasia.

Yet the peninsular and insular western extremity of the continent, thrusting toward the North Atlantic

Ocean, provides—thanks to its latitude and its physical geography—a relatively genial human habitat, and the

long processes of human history came to mark off the region as the home of a distinctive civilization. In

spite of its internal diversity, Europe has thus functioned, from the time it first emerged in the human

consciousness, as a world apart, concentrating—to borrow a phrase from Christopher Marlowe—“infinite riches

in a little room.”

As a conceptual construct, Europa, as the more learned of the ancient Greeks first conceived it, stood in

sharp contrast to both Asia and Libya, the name then applied to the known northern part of Africa.

Literally, Europa is now thought to have meant “Mainland,” rather than the earlier interpretation, “Sunset.”

It appears to have suggested itself to the Greeks, in their maritime world, as an appropriate designation

for the extensive northerly lands that lay beyond, lands with characteristics vaguely known yet clearly

different from those inherent in the concepts of Asia and Libya—both of which, relatively prosperous and

civilized, were associated closely with the culture of the Greeks and their predecessors. From the Greek

perspective then, Europa was culturally backward and scantily settled. It was a barbarian world—that is, a

non-Greek one, with its inhabitants making “bar-bar” noises in unintelligible tongues. Traders and travelers

also reported that the Europe beyond Greece possessed distinctive physical units, with mountain systems and

lowland river basins much larger than those familiar to inhabitants of the Mediterranean region. It was

clear as well that a succession of climates, markedly different from those of the Mediterranean borderlands,

were to be experienced as Europe was penetrated from the south. The spacious eastern steppes and, to the

west and north, primeval forests as yet only marginally touched by human occupancy further underlined

environmental contrasts.

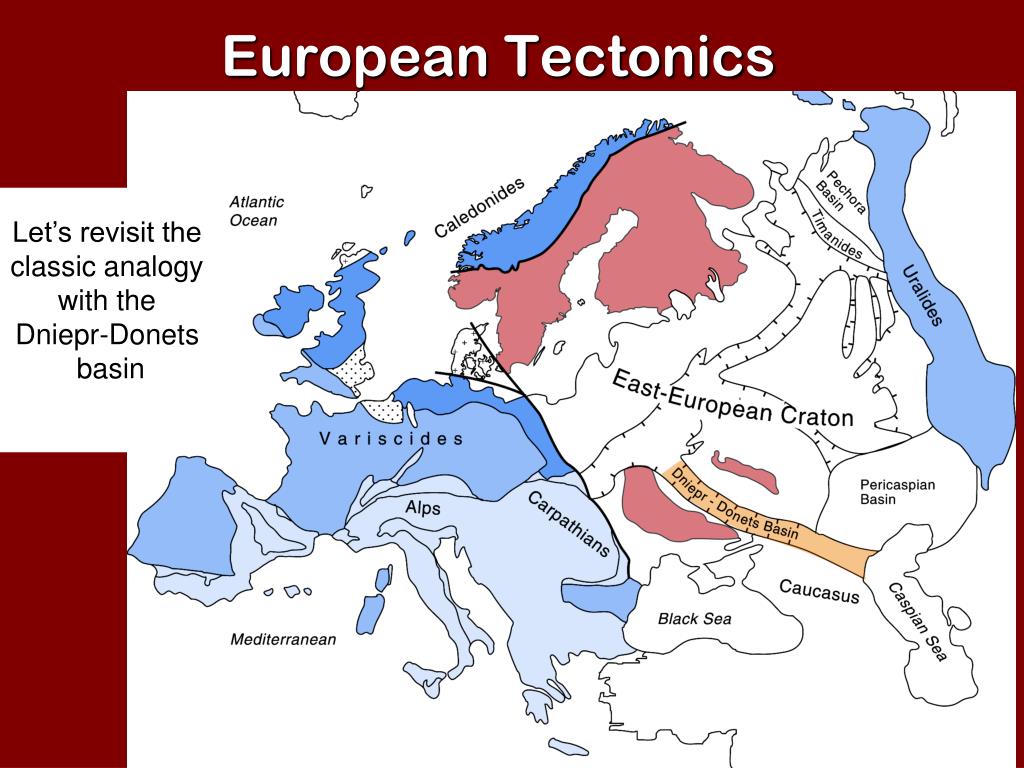

The geologic record of the continent of Europe is a classic example of how a continent has grown through

time. The Precambrian rocks in Europe range in age from about 3.8 billion to 541 million years. They are

succeeded by rocks of the Paleozoic Era, which continued to about 252 million years ago; of the Mesozoic

Era, which lasted until about 66 million years ago; and of the Cenozoic Era (i.e., the past 66 million

years). The present shape of Europe did not finally emerge until about 5 million years ago. The types of

rocks, tectonic landforms, and sedimentary basins that developed throughout the geologic history of Europe

strongly influence human activities today.

The largest area of oldest rocks in the continent is the Baltic Shield, which has been eroded down to a low

relief. The youngest rocks occur in the Alpine system, which still survives as high mountains. Between those

belts are basins of sedimentary rocks that form rolling hills, as in the Paris Basin and southeastern

England, or extensive plains, as in the Russian Platform. The North Sea is a submarine sedimentary basin on

the shallow-water continental margin of the Atlantic Ocean. Iceland is a unique occurrence in Europe: it is

a volcanic island situated on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge within the still-opening Atlantic Ocean.

Precambrian rocks occur in three basic tectonic environments. The first is in shields, like the Baltic

Shield, which are large areas of stable Precambrian rocks usually surrounded by later orogenic

(mountain-forming) belts. The second is as basement to younger coverings of Phanerozoic sediments (i.e.,

deposits that have been laid down since the beginning of the Paleozoic). For example, the sediments of the

Russian Platform are underlain by Precambrian basement, which extends from the Baltic Shield to the Ural

Mountains, and Precambrian rocks underlie the Phanerozoic sediments in southeastern England. The Ukrainian

Massif is an uplifted block of Precambrian basement that rises above the surrounding plain of younger

sediments. The third environment occurs as relicts (residual landforms) in younger orogenic belts. For

example, there are Precambrian rocks in the Bohemian Massif that are 1 billion years old and rocks in the

Channel Islands in the English Channel that are 1.6 billion years old, both of which are remnants from the

Middle Proterozoic Era within the late Paleozoic Hercynian belt. In the Hercynian belt in Bavaria, detrital

zircons have been dated to 3.84 billion years ago, but the source of those rocks is not known.

Paleozoic sedimentary rocks occur either in sedimentary basins like the Russian Platform—which has never

been affected by any periods of mountain formation and thus has sediments that are still flat-lying and

fossiliferous—or within orogenic belts such as the Caledonian and Hercynian, where they commonly have been

deformed by folding and thrusting, partly recrystallized, and subjected to intrusion by granites.

Mesozoic-Cenozoic sediments occur either in a well-preserved state in sedimentary basins unaffected by

orogenesis, as within the Russian Platform and under the North Sea, or in a highly deformed and

metamorphosed state, as in the Alpine system.

The geologic development of Europe may be summarized as follows. Archean rocks (those more than 2.5 billion

years old) are the oldest of the Precambrian and crop out in the northern Baltic Shield, Ukraine, and

northwestern Scotland. Two major Proterozoic (i.e., from about 2.5 billion to 541 million years ago)

orogenic belts extend across the central and southern Baltic Shield. Thus, the shield has a composite

origin, containing remnants of several Precambrian orogenic belts.

About 540 to 500 million years ago a series of new oceans opened, and their eventual closure gave rise to

the Caledonian, Hercynian, and Uralian orogenic belts. There is considerable evidence suggesting that those

belts developed by plate-tectonic processes, and they each have a history that lasted hundreds of millions

of years. Formation of the belts gave rise to the supercontinent of Pangea; its fragmentation, beginning

about 200 million years ago, gave rise to a new ocean, the Tethys Sea. Closure of that ocean about 50

million years ago, by subduction and plate-tectonic processes, led to the Alpine orogeny—e.g., the formation

of the Alpine orogenic system, which extends from the Atlantic Ocean to Turkey and contains many separate

orogenic belts (which remain as mountain chains), including the Pyrenees, the Baetic Cordillera, the Atlas

Mountains, the Swiss-Austrian Alps, the Apennine Range, the Carpathian Mountains, the Dinaric Alps, and the

Taurus and Pontic mountains. During the time that the Tethys was opening (about 180 million years ago), the

Atlantic Ocean also began to open

The Atlantic is still opening along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge under the ocean, with Iceland constituting an

area of the ridge that is raised above sea level. The youngest tectonic activity in Europe is represented by

the present-day volcanic eruptions in Iceland; by volcanoes such as Etna and Vesuvius; and by earthquakes,

as in the Aegean region and in the Alpine system, which result from current stresses between the Eurasian

and African plates.

A contrast exists between the configuration of peninsular, or western, Europe and that of eastern Europe, which is a much larger and more continental area. A convenient division is made by a line linking the base of the peninsula of Jutland with the head of the Adriatic Sea. The western part of the continent clearly has a high proportion of coastline with good maritime access and often with inland penetration by means of navigable rivers. Continental shelves—former land surfaces that have been covered by shallow seas—are a feature of peninsular Europe, while the coasts themselves are both submerged or drowned, as in southwestern Ireland and northwestern Spain, and emergent, as in western Scotland and southern Wales, where raised former beaches are in evidence. East of the Vistula River, Europe’s expansive lowlands have something of the scale and character of those of northern Asia. The continent also comprises numerous islands, some—notably the Faroes and Iceland—located at a distance from the mainland. Fortuitously, Europe has no continuous mountain obstacle aligned north-south, corresponding, for example, to the Western Cordillera of North America and the Andes Mountains of South America, that would limit access into western Europe from the ocean.

More than half of Europe consists of lowlands, standing mostly below 600 feet (180 metres) but infrequently

rising to 1,000 feet (300 metres). Most extensive between the Baltic and White seas in the north and the

Black, Azov, and Caspian seas in the south, the lowland area narrows westward, lying to the south of the

northwestern highlands; it is divided also by the English Channel and the mountains and plateaus of central

Europe. The Danubian and northern Italian lowlands are thus mountain-ringed islands. The northern lowlands

are areas of glacial deposition, and, accordingly, their surface is diversified by such features as the

Valdai Hills of western Russia; by deposits of boulder clay, sands, and gravels; by glacial lakes; and by

the Pripet Marshes, a large ill-drained area of Belarus and Ukraine. Another important physical feature is

the southeast-northwest zone of windblown loess deposits that have accumulated from eastern Britain to

Ukraine. The Börde (German: “edge”) belt lies at the northern foot of the Central European Uplands and the

Carpathians. Southward of the limits of the northern glacial ice are vales and hills, with the Paris and

London basins typical examples. Superficial rock cover, elevation, drainage, and soil have sharply

differentiated those lowlands—which are of prime importance to human settlement—into areas of marsh or fen,

clay vales, sand and gravel heaths, or river terraces and fertile plains.

The central uplands and plateaus present distinctive landscapes of rounded summits, steep slopes, valleys,

and depressions. Examples of such physiographic features can be found in the Southern Uplands of Scotland,

the Massif Central of France, the Meseta Central of Spain, and the Bohemian Massif. Routes detour around, or

seek gaps through, those uplands—whose German appellation, Horst (“thicket”), recalls their still wooded

character, while their coal basins give them great economic importance. The well-watered plateaus give rise

to many rivers and are well adapted to pastoral farming. Volcanic rocks add to the diversity of those

regions.

The ancient, often mineral-laden rocks of the northwestern highlands, their contours softened by prolonged

erosion and glaciation, are found throughout much of Iceland, in Ireland, and in northern and western

Britain and Scandinavia. Those highland areas include lands of abundant rainfall—which supplies

hydroelectricity and water to industrial cities—and provide summer pastures for cattle. The land in those

areas, however, is of little use for crops. The coasts of the northwestern highlands—and in particular the

fjords of Norway—invite maritime enterprise.

A world of peninsulas and islands, southern Europe is subject to its own climatic regime, with fragmented

but predominantly mountain and plateau landscapes. The Iberian Peninsula features interior tablelands of

Paleozoic rocks that are flanked by mountains of Alpine type. The restricted lowlands lie within interior

basins or fringe the coasts; those of Portugal, North Macedonia, Thrace (in the southeastern Balkans), and

northern Italy are relatively large. Runoff from the Alps furnishes much water for electricity-generating

stations as well as for the flow regimes of major rivers

As Francis Bacon, the great English Renaissance man of letters, aptly observed, “Every wind has its

weather.” It is air mass circulation that provides the main key to Europe’s climate, the more so since

masses of Atlantic Ocean origin can pass freely through the lowlands, except in the case of the Caledonian

mountains of Norway. Polar air masses derived from areas close to Iceland and tropical masses from the

Azores bring, respectively, very different conditions of temperature and humidity and produce different

climatic effects as they move eastward. Continental air masses from eastern Europe have equally easy access

westward. The almost continuous belt of mountains trending west-east across Europe also impedes the

interchange of tropical and polar air masses.

A scanty population of now-extinct hominin species (see Hominidae) lived in Europe before modern humans

appeared some 45,000–43,000 years ago. Throughout the prehistoric period the continent experienced continual

waves of immigration from Asia. In the modern period, especially since the mid-20th century, large numbers

of people have immigrated from other continents, particularly Africa and Asia. Nevertheless, Europe today

remains preeminently the homeland of various European peoples.

Efforts have been made to characterize different “ethnic types” among European peoples, but these are merely

selectively defined physical traits that, at best, have only a certain descriptive and statistical value. On

the other hand, territorial differences in language and other cultural aspects are well known, and these

have been of immense social and political import in Europe. These differences place Europe in sharp contrast

to such relatively recently colonized lands as the United States, Canada, and Australia. Given the agelong

habitation of its land and the minimal mobility of the peasantry—long the bulk of the population—Europe

became the home of many linguistic and national “core areas,” separated by mountains, forests, and

marshlands. Its many states, some long-established, introduced another divisive element that was augmented

by modern nationalistic sentiments.

Efforts to associate groups of states for specific defense and trade functions, especially after World War

II, created wider unitary associations but with fundamental east-west differences. Thus, there appeared two

clear-cut, opposing units—one centred on the Soviet Union and the other on the countries of western

Europe—as well as a number of relatively neutral states (Ireland, Sweden, Austria, Switzerland, Finland, and

Yugoslavia). This pattern was subsequently altered in the late 1980s and early 1990s with the dissolution of

the Soviet bloc (including the Soviet Union itself), the rapprochement between east and west, and the

creation and expansion of the European Union (EU).

There are some 160 culturally distinct groups in Europe, including a number of groups in the Caucasus region

that have affinities with both Asia and Europe. Each of these large groups exhibits two significant

features. First, each is characterized by a degree of self-recognition by its members, although the basis

for such collective identity varies from group to group. Second, each group—except the Jews and the Roma

(Gypsies)—tends to be concentrated and numerically dominant within a distinctive territorial homeland.

For a majority of groups the basis for collective identity is possession of a distinctive language or

dialect. The Catalans and Galicians of Spain, for example, have languages notably different from the

Castilian of the majority of Spaniards. On the other hand, some peoples may share a common language yet set

each other apart because of differences in religion. In the Balkan region, for instance, the Eastern

Orthodox Serbs, Muslim Bosnians (Bosniaks), and Roman Catholic Croats all speak a language that linguists

refer to as Serbo-Croatian; however, each group generally prefers to designate its language as Serbian,

Bosnian, or Croatian. Some groups may share a common language but remain separate from each other because of

differing historical paths. Thus, the Walloons of southern Belgium and the Jurassiens of the Jura in

Switzerland both speak French, yet they see themselves as quite different from the French because their

groups have developed almost completely outside the boundaries of France. Even when coexisting within the

same state, some groups may have similar languages and common religions but remain distinctive from each

other because of separate past associations. During Czechoslovakia’s 74 years as a single state, the

historical linkages of Slovaks with the Hungarian kingdom and Czechs with the Austrian Empire played a role

in keeping the two groups apart; the country was divided into two separate states, the Czech Republic and

Slovakia, in 1993.

The primary European cultural groups have been associated by ethnographers into some 21 culture areas. The

groupings are based primarily on similarities of language and territorial proximity. Although individuals

within a primary group generally are aware of their cultural bonds, the various groups within an

ethnographically determined culture area do not necessarily share any self-recognition of their affinities

to one another. This is particularly true in the Balkan culture area. Peoples in the Scandinavian and German

(German-language) culture areas, by contrast, are much more aware of belonging to broader regional

civilizations.

Within the complex of European languages, three major divisions stand out: Romance, Germanic, and Slavic.

All three are derived from a parent Indo-European language of the early migrants to Europe from southwestern

Asia.The Romance languages dominate western and Mediterranean Europe and include French, Spanish,

Portuguese, Italian, and Romanian, plus such lesser-known languages as Occitan (Provençal) in southern

France, Catalan in northeastern Spain and Andorra, and Romansh in southern Switzerland. All are derived from

the Latin language of the Roman Empire.The Germanic languages are found in central, northern, and

northwestern Europe. They are derived from a common tribal language that originated in southern Scandinavia,

and they include German, Dutch, Danish, Norwegian, Swedish, and Icelandic, as well as the minor Germanic

tongue of Frisian in the northern Netherlands and northwestern Germany. English is a Germanic language, but

about half its vocabulary has Romance origins.The Slavic languages are characteristic of eastern and

southeastern Europe and of Russia. These languages are usually divided into three branches: West, East, and

South. Among the West Slavic languages are Polish, Czech and Slovak, Upper and Lower Sorbian of eastern

Germany, and the Kashubian language of northern Poland. The East Slavic languages are Russian, Ukrainian,

and Belarusian. The South Slavic languages include Slovene, Serbo-Croatian (known as Serbian, Croatian, or

Bosnian), Macedonian, and Bulgarian.In addition to the three major divisions of the Indo-European languages,

three minor groups are also noteworthy. Modern Greek is the mother tongue of Greece and of the Greeks in

Cyprus, as well as the people of other eastern Mediterranean islands. Older forms of the language were once

widespread along the eastern and southern shores of the Mediterranean and in southern peninsular Italy and

Sicily. The Baltic language family includes modern Latvian and Lithuanian. The Old Prussian language also

belonged to the Baltic group but was supplanted by German through conquest and immigration. Europe’s Roma

speak the distinctive Romany language, which has its origins in the Indic branch of the Indo-European

languages.

The majority of primary culture groups in Europe have a single dominant religion, although the English,

German, Swiss, Hungarian, and Netherlandic groups are noteworthy for the coexistence of Roman Catholicism

and Protestantism. Like its languages, Europe’s religious divisions fall into three broad variants of a

common ancestor, plus distinctive faiths adhered to by smaller groups.

Most Europeans adhere to one of three broad divisions of Christianity: Roman Catholicism in the west and

southwest, Protestantism in the north, and Eastern Orthodoxy in the east and southeast. The divisions of

Christianity are the result of historic schisms that followed its period of unity as the adopted state

religion in the late stages of the Roman Empire. The first major religious split began in the 4th century,

when pressure from “barbarian” tribes led to the division of the empire into western and eastern parts. The

bishop of Rome became spiritual leader of the West, while the patriarch of Constantinople led the faith in

the East; the final break occurred in 1054. The line adopted to divide the two parts of the empire remains

very much a cultural discontinuity in the Balkan Peninsula today, separating Roman Catholic Croats,

Slovenes, and Hungarians from Eastern Orthodox Montenegrins, Serbs, Bulgarians, Romanians, and Greeks. The

second schism occurred in the 16th century within the western branch of the religion, when Martin Luther

inaugurated the Protestant Reformation. Although rebellion took place in many parts of western Europe

against the central church authority vested in Rome, the Reformation was successful mainly in the

Germanic-speaking areas of Britain, northern Germany, the Netherlands, Scandinavia, and the adjacent regions

of Finland, Estonia, and Latvia.Judaism has been practiced in Europe since Roman times. Jews undertook

continued migrations into and throughout Europe, in the process dividing into two distinct branches—the

Ashkenazi and the Sephardi. Although the Holocaust and emigration greatly reduced their numbers in

Europe—particularly in eastern Europe, where Jews once made up a large minority population—Jews are still

found in urban areas throughout the continent.Islam also has a long history in Europe. Islamic incursions

into the Iberian and Balkan peninsulas during the Middle Ages were influential in the cultures of those

regions. Muslim communities still exist in several parts of the Balkans, including Albania, Bosnia and

Herzegovina, and northeastern Bulgaria. In European Russia, Muslims are more numerous; among them are the

Kazan Tatars and the Bashkirs in the Volga-Ural region. Large Muslim communities exist in many western

European cities as well. The in-migration of guest workers from Asia, North Africa, Turkey, and the former

Yugoslavia during eras of labour shortages and economic expansion, particularly in the second half of the

20th century, contributed to the growth of these communities.

Topographic: climatic and human influences are mainly responsible for the present distribution of

natural

vegetation and of fauna. Climatic changes in Europe, especially those since the Ice Age, have left their

impact on the distribution of plants and animals. Man’s influence accounts for the fact that Europe’s

original forested area pf close to 85%, only one-third remains, much of it second growth or the scrub forest

of the Mediterranean area. The extensive grasslands of the southern parts of Russia also have been

intensively cultivated.

The original pattern or a clear-cut vegetation distribution from south to north is obscure; its remnants

areonly partly identifiable in the mountains. The distribution of Europe’s natural vegetation and fauna,

especially of the vegetation, is set in a zonal arrangement, closely related to present climatic zones,

though earlier climatic influences still have a minor impact. The zonal arrangement is less uniform for soil

distribution because its formation is determined not only by climate, but also by underlying rock material,

drainage conditions, vegetation, and temperature in relation to rainfall and evaporation. Following are the

major European vegetation zones with their soil, flora, and fauna characteristics.

Mediterranean Zone: The most widespread vegetation in the evergreen, small scrub forest, which has

various

names: maki in Corsica, maquis in France, and macchia in Italy. Important also are the oak (live and cork),

oleander, laurel, juniper, and a great variety of thorny plants that blossom in spring and are dormant

during the period of greatest heat. In higher altitudes, a few stands of chestnut, beech, and conifers from

former continuous stands have remained. Overpasturing and the use of wood for charcoal have destroyed most

forests and make reforestation difficult. The characteristic Mediterranean soil has red color (red

podsolics). When it has a deep profile, it is highly productive. In Italy it is named terra rossa (“red

earth”), but great differences exist depending on texture and on calcium or silica content. Alluvial

lowlands and areas under irrigation, such as the Po plains and the huertas (“gardens”) of Spain, are

intensively cultivated. Native plants such as the olive tree (which also grows wild), citrus, fig tree,

stone fruit trees, and some date palms are cultivated. Remaining animal species include mountain sheep, wild

goat, wild cat, and boar. Reptiles (vipers, snakes, turtles, lizards) are numerous.

Mixed Forest Zone: Broadleaf (deciduous) trees of this zone extend from northwestern Spain to the

British

Isles and southern Norway and to the western forelands of the Urals in the east. The zone is limited by

excessive heat toward the south and by excessive cold toward the north. Above approximately 60° N. lat.

northern (boreal) coniferous forests predominate. They also exist in higher altitudes of the Alpine

mountains. The beech, elm, maple, and oak in the west, and the chestnut and pine on sandy soils, are most

common. The beech, in combination with spruce and fir, predominates in central Europe, but in higher

altitudes a combination of pine and larch is widespread.

The oak, together with coniferous trees in the north and with grasslands in the south, is prevalent over all

of Eastern Europe. A variety of flora is found along the borders of the Mediterranean zone; different kinds

of heather are common along the Baltic marshes. Most of the soils belong to the various podsolized

subdivisions, with the color of the surface layers serving as the main characteristic. The most important

are the brown and gray forest soils, which are very fertile and have been under cultivation for generations.

Much of the original fauna has long been destroyed or reduced by man, including the wild ox, horse, bison,

elk, and furred animals. Today the chamois, wild goat, and marmot are most widespread in the mountainous

areas and the deer, fox, and badger throughout the entire zone.

Northern Forest Zone: This zone consists predominately of a spruce-fir combination with an

undergrowth of

mosses, and includes Europe’s largest timber-growing region. The zone thins out toward the tundra in the

north, where there are isolated stands of conifer and willow. The most common trees are the different

species of spruce, pine, larch, and fir. Most of the soils are unproductive, heavily leached, acid, and

often poorly drained and ash in color. The forests are rich in fur-bearing animals, including the bear, fox,

wolf, badger, deer, and a large variety of birds.

Tundra Zone: Only a narrow strip along the Artic Sea and in the Scandinavian highlands (fjeld) falls

within

this zone. It is characterized by a large number of mosses, sedges, lichens, and scattered growth of mostly

dwarf birch and willow. During the summer the tundra comes to life with a variety of blossoming plants. No

true soils can develop in the poorly drained surfaces and the edge of the tundra lies within the permafrost

region (perennially frozen soils). Fauna is restricted to the lemming, fox, and some wolves and bears on

land, and the seal, polar bear, and the occasional walrus in the artic seas. The reindeer lives in the broad

border zone to the south in winter, and uses the open tundra in summer only. The tundra is also home for

numerous mosquitoes, flies, and birds.

Steppe: The transitional zone of the steppe is particularly well developed in the lower Danube region

and

across southern European U.S.S.R. In the north it is referred to as forest steppe because of the scattering

of oak forests amid the open grasslands. Farther south the open grasslands, with characteristic black soil

(Russ. Chernozem, “black earth”), lend themselves well to the growth of cereals. Toward the southeast the

grasslands become more and more scattered and turn to semidesert, with rainfall of less than 10 in. only in

the extreme southeast of European U.S.S.R.

Made from ❤️ by Divyesh Idhate