North America, third largest of the world’s continents, lying for the most part between the Arctic Circle and the Tropic of Cancer. It extends for more than 5,000 miles (8,000 km) to within 500 miles (800 km) of both the North Pole and the Equator and has an east-west extent of 5,000 miles. It covers an area of 9,355,000 square miles (24,230,000 square km).North America occupies the northern portion of the landmass generally referred to as the New World, the Western Hemisphere, or simply the Americas. Mainland North America is shaped roughly like a triangle, with its base in the north and its apex in the south; associated with the continent is Greenland, the largest island in the world, and such offshore groups as the Arctic Archipelago, the West Indies, Haida Gwaii (formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands), and the Aleutian Islands.

North America is bounded on the north by the Arctic Ocean, on the east by the North Atlantic Ocean, on the

south by the Caribbean Sea, and on the west by the North Pacific Ocean. To the northeast Greenland is

separated from Iceland by the Denmark Strait, and to the northwest Alaska is separated from the Asian

mainland by the much narrower Bering Strait. North America’s only land connection is to South America at the

narrow Isthmus of Panama. Denali (Mount McKinley) in Alaska, rising 20,310 feet (6,190 metres) above sea

level, is the continent’s highest point, and Death Valley in California, at 282 feet (86 metres) below sea

level, is its lowest. North America’s coastline of some 37,000 miles (60,000 km)—the second longest of the

continents after Asia—is notable for the great number of indentations, particularly in the northern half.

The name America is derived from that of the Italian merchant and navigator Amerigo Vespucci, one of the

earliest European explorers to visit the New World. Although at first the term America was applied only to

the southern half of the continent, the designation soon was applied to the entire landmass. Those portions

that widened out north of the Isthmus of Panama became known as North America, and those that broadened to

the south became known as South America. According to some authorities, North America begins not at the

Isthmus of Panama but at the narrows of Tehuantepec, with the intervening region called Central America.

Under such a definition, part of Mexico must be included in Central America, although that country lies

mainly in North America proper. To overcome this anomaly, the whole of Mexico, together with Central and

South American countries, also may be grouped under the name Latin America, with the United States and

Canada being referred to as Anglo-America. This cultural division is a very real one, yet Mexico and Central

America (including the Caribbean) are bound to the rest of North America by strong ties of physical

geography. Greenland also is culturally divided from, but physically close to, North America. Some

geographers characterize the area roughly from the southern border of the United States to the northern

border of Colombia as Middle America, which differs from Central America because it includes Mexico. Some

definitions of Middle America also include the West Indies.

North America contains some of the oldest rocks on Earth. Its geologic structure is built around a stable

platform of Precambrian rock called the Canadian (Laurentian) Shield. To the southeast of the shield rose

the ancient Appalachian Mountains; and to the west rose the younger and considerably taller Cordilleras,

which occupy nearly one-third of the continent’s land area. In between these two mountain belts are the

generally flat regions of the Great Plains in the west and the Central Lowlands in the east.

The continent is richly endowed with natural resources, including great mineral wealth, vast forests,

immense quantities of fresh water, and some of the world’s most fertile soils. These have allowed North

America to become one of the most economically developed regions in the world, and its inhabitants enjoy a

high standard of living. North America has the highest average income per person of any continent and an

average food intake per person that is significantly greater than that of other continents. Although it is

home to less than 10 percent of the world’s population, its per capita consumption of energy is almost four

times as great as the world average.

North America’s first inhabitants are believed to have been ancient Asiatic peoples who migrated from Siberia to North America sometime during the last glacial advance, known as the Wisconsin Glacial Stage, the most recent major division of the Pleistocene Epoch (about 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago). The descendants of these peoples, the various Native American and Eskimo (Inuit) groups, largely have been supplanted by peoples from the Old World. People of European ancestry constitute the largest group, followed by those of African and of Asian ancestry; in addition there is a large group of Latin Americans, who are of mixed European and Native American ancestry.

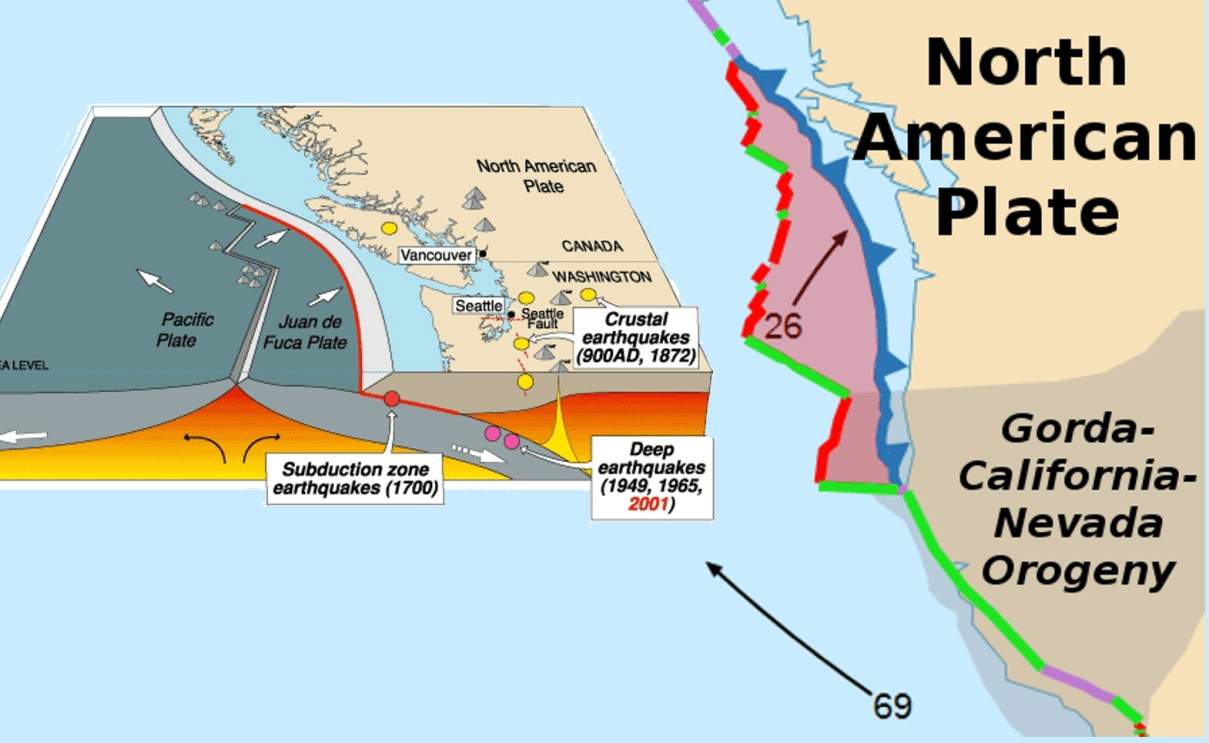

Continents have collided and broken apart repeatedly over geologic time. When they separate, new ocean

basins develop between the diverging pieces through the process of seafloor spreading. Spreading, which

originates at oceanic ridges, is compensated (to conserve surface area on the planet) by subduction—the

process whereby the seafloor flexes and sinks along inclined trajectories into the Earth’s interior—at

deep-sea trenches. Closure of ocean basins by subduction of the seafloor results in continental

collisions.The material moved laterally from spreading ridges to subduction zones includes plates of

rock up to 60 miles (100 km) thick. This rigid outer shell of the Earth is called the lithosphere, as

distinct from the underlying hotter and more fluid asthenosphere. The portions of lithospheric plates

descending into the asthenosphere at subduction zones are called slabs. The many lithospheric plates

that make up the present surface of the Earth are bounded by an interlinking system of oceanic ridges,

subduction zones, and laterally moving fractures known as transform faults. Over geologic time the

system of plate boundaries has continually evolved as new plates have formed, expanded, contracted, and

disappeared.

North America occupies the northern portion of the landmass generally referred to as the New World, the

Western Hemisphere, or simply the Americas. Mainland North America is shaped roughly like a triangle,

with its base in the north and its apex in the south; associated with the continent is Greenland, the

largest island in the world, and such offshore groups as the Arctic Archipelago, the West Indies, Haida

Gwaii (formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands), and the Aleutian Islands.

North America is bounded on the north by the Arctic Ocean, on the east by the North Atlantic Ocean, on

the south by the Caribbean Sea, and on the west by the North Pacific Ocean. To the northeast Greenland

is separated from Iceland by the Denmark Strait, and to the northwest Alaska is separated from the Asian

mainland by the much narrower Bering Strait. North America’s only land connection is to South America at

the narrow Isthmus of Panama. Denali (Mount McKinley) in Alaska, rising 20,310 feet (6,190 metres) above

sea level, is the continent’s highest point, and Death Valley in California, at 282 feet (86 metres)

below sea level, is its lowest. North America’s coastline of some 37,000 miles (60,000 km)—the second

longest of the continents after Asia—is notable for the great number of indentations, particularly in

the northern half.

The name America is derived from that of the Italian merchant and navigator Amerigo Vespucci, one of the

earliest European explorers to visit the New World. Although at first the term America was applied only

to the southern half of the continent, the designation soon was applied to the entire landmass. Those

portions that widened out north of the Isthmus of Panama became known as North America, and those that

broadened to the south became known as South America. According to some authorities, North America

begins not at the Isthmus of Panama but at the narrows of Tehuantepec, with the intervening region

called Central America. Under such a definition, part of Mexico must be included in Central America,

although that country lies mainly in North America proper. To overcome this anomaly, the whole of

Mexico, together with Central and South American countries, also may be grouped under the name Latin

America, with the United States and Canada being referred to as Anglo-America. This cultural division is

a very real one, yet Mexico and Central America (including the Caribbean) are bound to the rest of North

America by strong ties of physical geography. Greenland also is culturally divided from, but physically

close to, North America. Some geographers characterize the area roughly from the southern border of the

United States to the northern border of Colombia as Middle America, which differs from Central America

because it includes Mexico. Some definitions of Middle America also include the West Indies.

North America contains some of the oldest rocks on Earth. Its geologic structure is built around a

stable platform of Precambrian rock called the Canadian (Laurentian) Shield. To the southeast of the

shield rose the ancient Appalachian Mountains; and to the west rose the younger and considerably taller

Cordilleras, which occupy nearly one-third of the continent’s land area. In between these two mountain

belts are the generally flat regions of the Great Plains in the west and the Central Lowlands in the

east.

The continent is richly endowed with natural resources, including great mineral wealth, vast forests,

immense quantities of fresh water, and some of the world’s most fertile soils. These have allowed North

America to become one of the most economically developed regions in the world, and its inhabitants enjoy

a high standard of living. North America has the highest average income per person of any continent and

an average food intake per person that is significantly greater than that of other continents. Although

it is home to less than 10 percent of the world’s population, its per capita consumption of energy is

almost four times as great as the world average.

North America’s first inhabitants are believed to have been ancient Asiatic peoples who migrated from

Siberia to North America sometime during the last glacial advance, known as the Wisconsin Glacial Stage,

the most recent major division of the Pleistocene Epoch (about 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago). The

descendants of these peoples, the various Native American and Eskimo (Inuit) groups, largely have been

supplanted by peoples from the Old World. People of European ancestry constitute the largest group,

followed by those of African and of Asian ancestry; in addition there is a large group of Latin

Americans, who are of mixed European and Native American ancestry.

The material moved laterally from spreading ridges to subduction zones includes plates of rock up to 60

miles (100 km) thick. This rigid outer shell of the Earth is called the lithosphere, as distinct from

the underlying hotter and more fluid asthenosphere. The portions of lithospheric plates descending into

the asthenosphere at subduction zones are called slabs. The many lithospheric plates that make up the

present surface of the Earth are bounded by an interlinking system of oceanic ridges, subduction zones,

and laterally moving fractures known as transform faults. Over geologic time the system of plate

boundaries has continually evolved as new plates have formed, expanded, contracted, and disappeared.

The outermost layer of the lithosphere is called the crust. It is composed of low-density material

crystallized from molten rock (magma) produced by partial melting of the lithosphere or asthenosphere.

The average thickness of the oceanic crust is about 4 miles (6.4 km). Oceanic plateaus and seamounts are

localized areas of abnormally thick oceanic crust that have resulted from submarine volcanism promoted

by hot jets of magma, or plumes, rising from deep within the Earth’s interior (i.e., from the mantle).

Oceanic crust is transient, being formed at the oceanic ridges and destroyed at the trenches. It has a

mean age of about 60 million years.Continental crust is thicker, 22 miles (35 km) on average and less

dense than oceanic crust, which accounts for its mean surface elevation of about 3 miles (4.8 km) above

that of the ocean floor (Archimedes’ principle). Continental crust is more complex than oceanic crust in

its structure and origin and is formed primarily at subduction zones. Lateral growth occurs by the

addition of rock scraped off the top of oceanic plates as they are subducted beneath continental

margins. Such margins are marked by lines of volcanoes, often in volcanic arcs, that form additions to

the crust—the result of partial melting of the wedge of the asthenosphere situated above the descending

slab and below the continental plate (melting is promoted by the release of water from the slab, which

lowers the melting point in the wedge). Subduction zones located within ocean basins (where one oceanic

plate descends beneath another) also generate volcanic arcs; these are called island arcs. Island arcs

consist of materials that tend to be transitional between oceanic and continental crust in both

thickness and composition. The first continents appear to have formed by accretion of various island

arcs.

Continental crust resists subduction. Consequently, the mean age of the continents is almost two billion

years, more than 30 times the average age of the oceanic crust. Thus, continents are the prime

repositories of information concerning Earth’s geologic evolution, but understanding their formation

requires knowledge of processes in the ocean basins from which they evolved

For millions of years Australia was part of the supercontinent of Pangaea and subsequently its southern

segment, Gondwanaland (or Gondwana). Its separate existence was finally assured by the severing of the

last connection between Tasmania and Antarctica, but it has been drifting toward the Southeast Asian

landmass. As a continent, Australia thus encompasses two extremes: on the one hand, it contains the

oldest known earth material while, on the other, it has stood as a free continent only since about 35

million years ago and is in the process—in terms of geologic time—of merging with Asia, so that its life

span as a continent will be of relatively short duration.

Although the geologic processes that shaped the North American continent have been so important that the 19th-century American historian Frederick Jackson Turner once contended that the life of America flowed down the arteries of its geology, the continent nevertheless is mainly seen through its climate, soils, and vegetation. The resultant physiographic regions dominate the contemporary geography of the continentThe central shield, named the Canadian or Laurentian Shield by geologists, consists of a low plateau (averaging about 1,400 feet [400 metres] in elevation) that is tilted at its edges and is most depressed at Hudson Bay, its centre. It has a rough surface of old, worn mountains and domes that rise above flat, geologically ancient basins. The shield represents an area that has undergone extensive erosion and sculpting by ice and weathering processes. The southern edge has the mountainous Algomans and Laurentians (more than 2,000 feet [600 metres] high) and rises to above 5,000 feet (1,500 metres) in the great dome of the Adirondacks. The eastern edge is somewhat higher, rising to nearly 6,000 feet (1,800 metres) in the Torngats and more than 7,000 feet (2,100 metres) on Baffin Island; in Greenland too it tilts up to more than 6,000 feet. The western rim is much lower, reaching only about 600 feet (180 metres) in parts. The Snare and Nonacho ranges west of Hudson Bay lift the edge of the plateau to nearly 2,000 ft. Faulting broke the northern rim into a series of prongs, extending into southeastern Ellesmere Island and across Victoria Island, with sea-drowned channels and low sedimentary basins in between, forming the Canadian Arctic Archipelago.The entire shield was under successive ice sheets during the Pleistocene Epoch (about 2,600,000 to 11,700 years ago), and its high eastern rim still contains relics of these glacial advances and retreats. Ice-cut valleys in the higher areas, ice-plucked basins everywhere, and ice-deposited ridges known as eskers and drumlins point to a major centre of ice accumulation and dispersion over central Labrador, still noted for its heavy snow cover. This is where the great continental glaciers originated. Greenland also was a main centre of glacial advance and retreat, while Keewatin in western Canada was an important secondary focus. Much of the shield has been scraped bare by glacial erosion; smooth, bare bedrock surfaces are commonplace. After most of the ice had melted and its tremendous weight had been lifted from the crust, portions of the shield began to rise, leaving traces of former beaches along the coasts of Greenland, Baffin Island, Labrador, and the Gulf of St. Lawrence; these provided narrow but vital benches for human settlement. Ice-cut rock basins have left countless lakes, and parts of the surface of the central shield are almost more water than land.

The enormous width of the continent in the higher latitudes has led to a great extension of Arctic and

cool temperate climates, while the tapering south has greatly reduced the land area under tropical

climates. Most storms are driven from west to east by a strong mid-continental airflow called the jet

stream, and these storms most often converge on the New England region. Thus, the Cordilleras of Canada

and the United States have climatically wet, windward slopes facing the Pacific and dry, leeward slopes

facing the interior.

In global terms, North America long remained a relatively empty and economically undeveloped land until

about 1500 CE. After that the continent began to receive great numbers of people from the Old

World—primarily Europe and Africa—and it underwent a profound transformation. The discussion that

follows primarily covers the nonindigenous peoples of mainland North America. The ethnohistory of the

North American Indians is treated in more detail in the article Native American, and that of the

Mesoamerican peoples is discussed in Pre-Columbian Civilizations; for treatment of the peoples in the

Caribbean region, see West Indies.

The date of the arrival in North America of the initial wave of peoples from whom the American Indians

(or Native Americans) emerged is still a matter of considerable uncertainty. According to prevailing

thought, it is relatively certain that they were Asiatic peoples who originated in northeastern Siberia

and crossed the Bering Strait (perhaps when it was a land bridge) into Alaska and then gradually

dispersed throughout the Americas. The glaciations of the Pleistocene Epoch (about 1,800,000 to 11,700

years ago) coincided with the evolution of modern humans, and ice sheets blocked ingress into North

America for extended periods of time. It was only during the interglacial periods that people ventured

into this unpopulated land. Some scholars claim an arrival about 60,000 years ago, before the last

glacial advance (Wisconsin Glacial Stage). The latest possible date now seems to be about 20,000 years

ago, with some pioneers filtering in during a recession in the Wisconsin glaciation.

These prehistoric invaders were Stone Age hunters who led a nomadic life, a pattern that many retained

until the coming of Europeans. As they worked their way southward from a narrow, ice-free corridor in

what is now the state of Alaska into the broad expanse of the continent—between what are now Florida and

California—the various communities tended to fan out and to hunt and forage in comparative isolation.

Until they converged in the narrows of southern Mexico and the confined spaces of Central America, there

was little of the fierce competition or the close interaction among groups that might have stimulated

cultural inventiveness. Although great architectural and scientific advances did occur in Mesoamerica,

there was markedly less in the way of metallurgy, transportation networks, and complex commerce than

among the contemporary civilizations of Asia, Europe, and sections of Africa. Cities appeared first

among the Olmec in the strategic narrows between Mexico and Central America and among the Maya in

portions of Guatemala, the Yucatán Peninsula, and Honduras. Subsequently, the Toltec and Aztec created

some remarkable cities in the high Mexican Plateau and developed a society whose crafts and general

sophistication rivaled those of Europe. These dense populations were based on a productive agriculture

that relied heavily on corn (maize), beans, and squash, along with a great variety of other vegetables

and fruits, fibres, dyes, and stimulants but almost no livestock.

The size of the pre-Columbian aboriginal population of North America remains uncertain, since the widely

divergent estimates have been based on inadequate data. Luis de Velasco, a 16th-century viceroy of New

Spain (Mexico), put the total for the West Indies, Mexico, and Central America at about 5,000,000; some

modern scholars, however, have suggested a figure two to five times larger for the year 1492. The

pre-Columbian population of what is now the United States and Canada, with its more widely scattered

societies, has been variously estimated at somewhere between 600,000 and 2,000,000. By that time, the

Indians there had not yet adopted intensive agriculture or an urban way of life, although the

cultivation of corn, beans, and squash supplemented hunting and fishing throughout the Mississippi and

Ohio river valleys and in the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence River region, as well as along the Gulf of Mexico

and Atlantic Coastal Plain. In those areas, semisedentary peoples had established villages, and, among

the Iroquois and the Cherokee, powerful federations of tribes had been formed. Elsewhere, however, on

the Great Plains, the Canadian Shield, the northern Appalachians, the Cordilleras, the Great Basin, and

the Pacific Coast, hunting, fishing, and gathering constituted the basic economic activity; and, in most

instances, extensive territories were needed to feed and support small groups.

The history of the entire aboriginal population of North America after the Spanish conquest has been one

of unmitigated tragedy. The combination of susceptibility to Old World diseases, loss of land, and the

disruption of cultural and economic patterns caused a drastic reduction in numbers—indeed, the

extinction of many communities. It is only since about 1900 that the numbers of some Native American

peoples have begun to rebound.

Although English is not Australia’s official language, it is effectively the de facto national language

and is almost universally spoken. Nevertheless, there are hundreds of Aboriginal languages, though many

have become extinct since 1950, and most of the surviving languages have very few speakers. Mabuiag,

spoken in the western Torres Strait Islands, and the Western Desert language have about 8,000 and 4,000

speakers, respectively, and about 50,000 Aboriginal people may still have some knowledge of an

Australian language. (For full discussion, see Australian Aboriginal languages.) The languages of

immigrant groups in Australia are also spoken, most notably Chinese, Italian, and Greek.

At least 7,000 species and subspecies of indigenous US flora have been categorized. The eastern forests

contain a mixture of softwoods and hardwoods that includes pine, oak, maple, spruce, beech, birch,

hemlock, walnut, gum, and hickory. The central hardwood forest, which originally stretched unbroken from

Cape Cod to Texas and northwest to Minnesota—still an important timber source—supports oak, hickory,

ash, maple, and walnut. Pine, hickory, tupelo, pecan, gum, birch, and sycamore are found in the southern

forest that stretches along the Gulf coast into the eastern half of Texas. The Pacific forest is the

most spectacular of all because of its enormous redwoods and Douglas firs. In the southwest are saguaro

(giant cactus), yucca, candlewood, and the Joshua tree.

The central grasslands lie in the interior of the continent, where the moisture is not sufficient to

support the growth of large forests. The tall grassland or prairie (now almost entirely under

cultivation) lies to the east of the 100th meridian. To the west of this line, where rainfall is

frequently less than 50 cm (20 in) per year, is the short grassland. Mesquite grass covers parts of west

Texas, southern New Mexico, and Arizona. Short grass may be found in the highlands of the latter two

states, while tall grass covers large portions of the coastal regions of Texas and Louisiana and occurs

in some parts of Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida. The Pacific grassland includes northern Idaho, the

higher plateaus of eastern Washington and Oregon, and the mountain valleys of California.

The intermontane region of the Western Cordillera is for the most part covered with desert shrubs.

Sagebrush predominates in the northern part of this area, creosote in the southern, with saltbrush near

the Great Salt Lake and in Death Valley.

The lower slopes of the mountains running up to the coastline of Alaska are covered with coniferous

forests as far north as the Seward Peninsula. The central part of the Yukon Basin is also a region of

softwood forests. The rest of Alaska is heath or tundra. Hawaii has extensive forests of bamboo and

ferns. Sugarcane and pineapple, although not native to the islands, now cover a large portion of the

cultivated land.

Small trees and shrubs common to most of the United States include hackberry, hawthorn, serviceberry,

blackberry, wild cherry, dogwood, and snowberry. Wildflowers bloom in all areas, from the seldom-seen

blossoms of rare desert cacti to the hardiest alpine species. Wildflowers include forget-me-not, fringed

and closed gentians, jack-in-the-pulpit, black-eyed Susan, columbine, and common dandelion, along with

numerous varieties of aster, orchid, lady's slipper, and wild rose.

An estimated 432 species of mammals characterize the animal life of the continental United States. Among

the larger game animals are the white-tailed deer, moose, pronghorn antelope, bighorn sheep, mountain

goat, black bear, and grizzly bear. The Alaskan brown bear often reaches a weight of 1,200–1,400 lbs.

Some 25 important furbearers are common, including the muskrat, red and gray foxes, mink, raccoon,

beaver, opossum, striped skunk, woodchuck, common cottontail, snowshoe hare, and various squirrels.

Human encroachment has transformed the mammalian habitat over the last two centuries. The American

buffalo (bison), millions of which once roamed the plains, is now found only on select reserves. Other

mammals, such as the elk and gray wolf, have been restricted to much smaller ranges.

Year-round and migratory birds abound. Loons, wild ducks, and wild geese are found in lake country;

terns, gulls, sandpipers, herons, and other seabirds live along the coasts. Wrens, thrushes, owls,

hummingbirds, sparrows, woodpeckers, swallows, chickadees, vireos, warblers, and finches appear in

profusion, along with the robin, common crow, cardinal, Baltimore oriole, eastern and western

meadowlarks, and various blackbirds. Wild turkey, ruffed grouse, and ring-necked pheasant (introduced

from Europe) are popular game birds.

Lakes, rivers, and streams teem with trout, bass, perch, muskellunge, carp, catfish, and pike; sea bass,

cod, snapper, and flounder are abundant along the coasts, along with such shellfish as lobster, shrimp,

clams, oysters, and mussels. Garter, pine, and milk snakes are found in most regions. Four poisonous

snakes survive, of which the rattlesnake is the most common. Alligators appear in southern waterways and

the Gila monster makes its home in the Southwest.

Laws and lists designed to protect threatened and endangered flora and fauna have been adopted

throughout the United States. Generally, each species listed as protected by the federal government is

also protected by the states, but some states may list species not included on federal lists or on the

lists of neighboring states. (Conversely, a species threatened throughout most of the United States may

be abundant in one or two states.) As of August 2003, the US Fish and Wildlife Service listed 987

endangered US species (up from 751 listed in 1996), including 65 mammals (64 in 1996), 78 birds (77 in

1996), 71 fish (69 in 1996), and 599 plants (432 in 1996); and 276 threatened species (209 in 1996),

including 147 plants (94 in 1996). The agency listed another 517 endangered and 41 threatened foreign

species by international agreement.

Threatened species, likely to become endangered if recent trends continue, include such plants as Lee

pincushion cactus. Among the endangered floral species (in imminent danger of extinction in the wild)

are the Virginia round-leaf birch, San Clemente Island broom, Texas wild-rice, Furbish lousewort,

Truckee barberry, Sneed pincushion cactus, spineless hedgehog

.

Endangered mammals included the red wolf, black-footed ferret, jaguar, key deer, northern swift fox, San

Joaquin kit fox, jaguar, jaguarundi, Florida manatee, ocelot, Florida panther, Utah prairie dog, Sonoran

pronghorn, and numerous whale species. Endangered species of rodents included the Delmarva Peninsula fox

squirrel, beach mouse, salt-marsh harvest mouse, 7 species of bat (Virginia and Ozark big-eared

Sanborn's and Mexican long-nosed, Hawaiian hoary, Indiana, and gray), and the Morro Ba, Fresno,

Stephens', and Tipton Kangaroo rats and rice rat.

Endangered species of birds included the California condor, bald eagle, three species of falcon

(American peregrine, tundra peregrine, and northern aplomado), Eskimo curlew, two species of crane

(whooping and Mississippi sandhill), three species of warbler (Kirtland's, Bachman's, and

golden-cheeked), dusky seaside sparrow, light-footed clapper rail, least tern, San Clemente loggerhead

shrike, bald eagle (endangered in most states, but only threatened in the Northwest and the Great Lakes

region), Hawaii creeper, Everglade kite, California clapper rail, and red-cockaded woodpecker.

Endangered amphibians included four species of salamander (Santa Cruz long-toed, Shenandoah, desert

slender, and Texas blind), Houston and Wyoming toad, and six species of turtle (green sea, hawksbill,

Kemp's ridley, Plymouth and Alabama red-bellied, and leatherback). Endangered reptiles included the

American crocodile, (blunt nosed leopard and island night), and San Francisco garter snake.

Aquatic species included the shortnose sturgeon, Gila trout, eight species of chub (humpback,

Pahranagat, Yaqui, Mohave tui, Owens tui, bonytail, Virgin River, and Borax lake), Colorado River

squawfish, five species of dace (Kendall Warm Springs, and Clover Valley, Independence Valley, Moapa and

Ash Meadows speckled), Modoc sucker, cui-ui, Smoky and Scioto madtom, seven species of pupfish (Leon

Springs, Gila Desert, Ash Meadows Amargosa, Warm Springs, Owens, Devil's Hole, and Comanche Springs),

Pahrump killifish, four species of gambusia (San Marcos, Pecos, Amistad, Big Bend, and Clear Creek), six

species of darter (fountain, watercress, Okaloosa, boulder, Maryland, and amber), totoaba, and 32

species of mussel and pearly mussel. Also classified as endangered were two species of earthworm

(Washington giant and Oregon giant), the Socorro isopod, San Francisco forktail damselfly, Ohio emerald

dragonfly, three species of beetle (Kretschmarr Cave, Tooth Cave, and giant carrion), Belkin's dune

tabanid fly, and 10 species of butterfly (Schaus' swallowtail, lotis, mission, El Segundo, and Palos

Verde blue, Mitchell's satyr, Uncompahgre fritillary, Lange's metalmark, San Bruno elfin, and Smith's

blue).

Several species on the federal list of endangered and threatened wildlife and plants are found only in

Hawaii. Endangered bird species in Hawaii included the Hawaiian dark-rumped petrel, Hawaiian gallinule,

Hawaiian crow, three species of thrush (Kauai, Molokai, and puaiohi), Kauai 'o'o, Kauai nukupu'u, Kauai

'alialoa, 'akiapola'au, Maui'akepa, Molokai creeper, Oahu creeper, palila, and 'o'u.

Endangered plants in the United States include: aster, cactus, pea, mustard, mint, mallow, bellflower

and pink family, snapdragon, and buckwheat.

Threatened fauna include the grizzly bear, southern sea otter, Newell's shearwater, eastern indigo

snake, bayou darter, several southwestern trout species, and Schaus swallowtail butterfly. Species

formerly listed as threatened or endangered that have been removed from the list include (with delisting

year and reason) American alligator (1987, recovered); coastal cutthroat trout (2000, taxonomic

revision); Bahama swallowtail butterfly (1984, amendment); gray whale (1994, recovered); brown pelican

(1984, recovered); Rydberg milk-vetch (1987, new information); Lloyd's hedgehog cactus (1999, taxonomic

revision), and Columbian white-tailed Douglas County Deer (2003, recovered).

Made from ❤️ by Divyesh Idhate